Recognize

With civilian harm reaching alarming levels across a record number of global conflicts in 2024, some situations of armed conflict received less public attention than others. There is a risk that such situations become chronically neglected on the world stage in terms of diplomatic, financial, and humanitarian engagement. In the longer term, civilians will suffer the consequences of such neglect. CIVIC considers situations underrecognized when levels of media coverage, attention from foreign donors or development partners, and political engagement at the regional and international levels are disproportionately low, compared to the harm that civilians experience.

Media

Despite the increasing importance of social media channels, traditional media coverage still plays a critical role in driving both public and political interest in conflicts. The level of violence, however, does not always align with the amount of media attention a particular context receives. In recent years, for example, the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza have largely dominated international news bulletins, while countries such as the DRC, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Yemen have received much less attention, despite the staggering levels of civilian deaths, displacement, and other harms.1

There are many, often overlapping, reasons why some conflicts are lower on the global media agenda. Visions of Humanity has highlighted how economic development plays a key role in driving media interest in conflict situations. A recent study showed that the median number of articles per death in high-income countries was 1,663, nearly 100 times more than the 17.4 articles per death in low-income countries.2 Another key factor is the perceived global significance of a conflict. Consequently, interstate wars also tend to receive more media attention than intrastate wars, which are often viewed as having smaller global stakes, even when civilian harm reaches catastrophic levels. According to CARE, the ten most neglected humanitarian crises in 2024 were all in Sub-Saharan Africa, based on an analysis of global, multilingual media coverage of 43 crisis situations each affecting at least one million people. These included several countries experiencing armed conflict with high levels of civilian casualties and displacement in 2024, including the CAR, Burkina Faso, and Niger.3 Burkina Faso, in particular, faced the worst humanitarian crisis in its history last year, exacerbated by a blockade imposed by armed groups in some regions that cut almost two million people off from aid.4

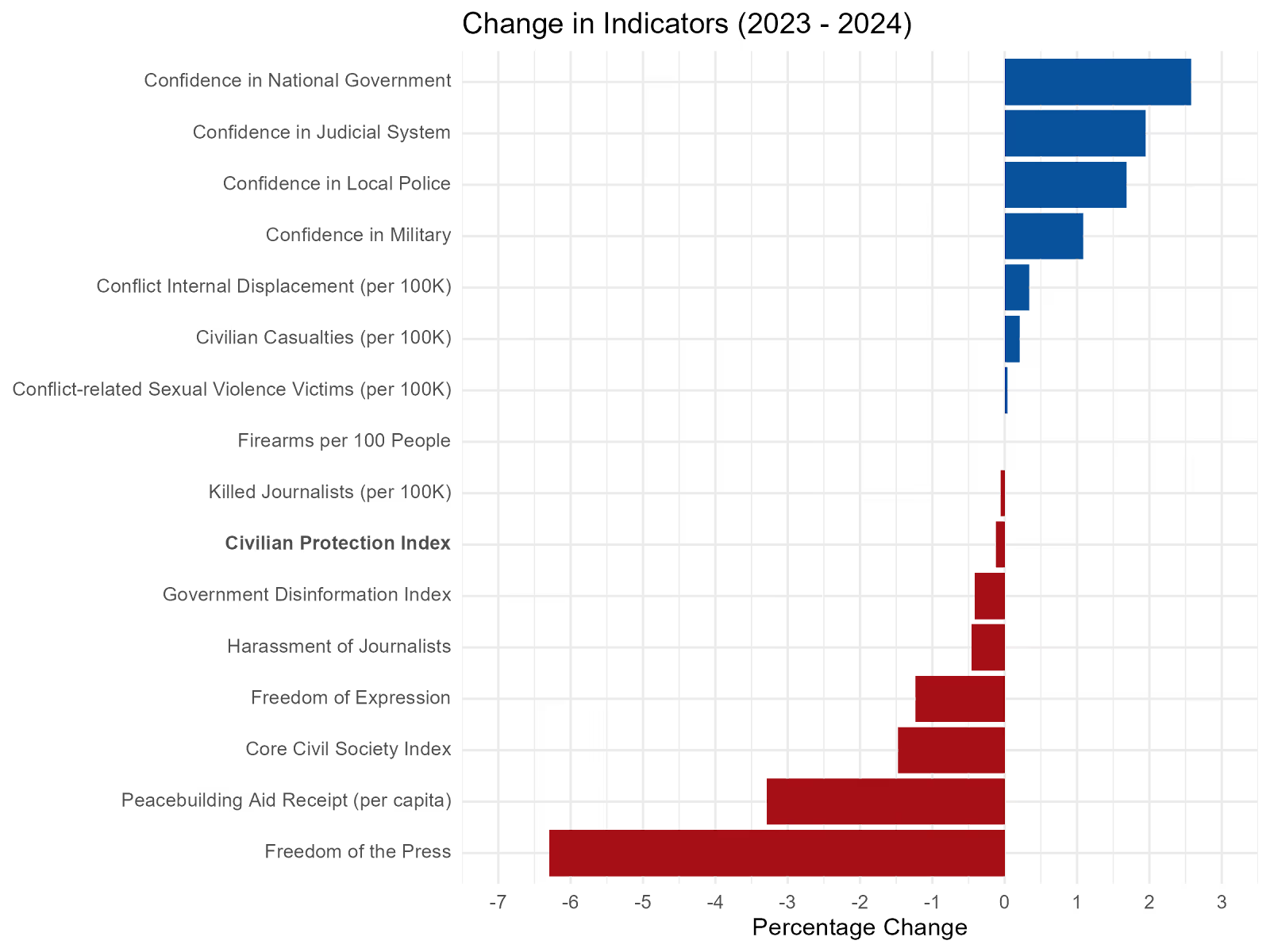

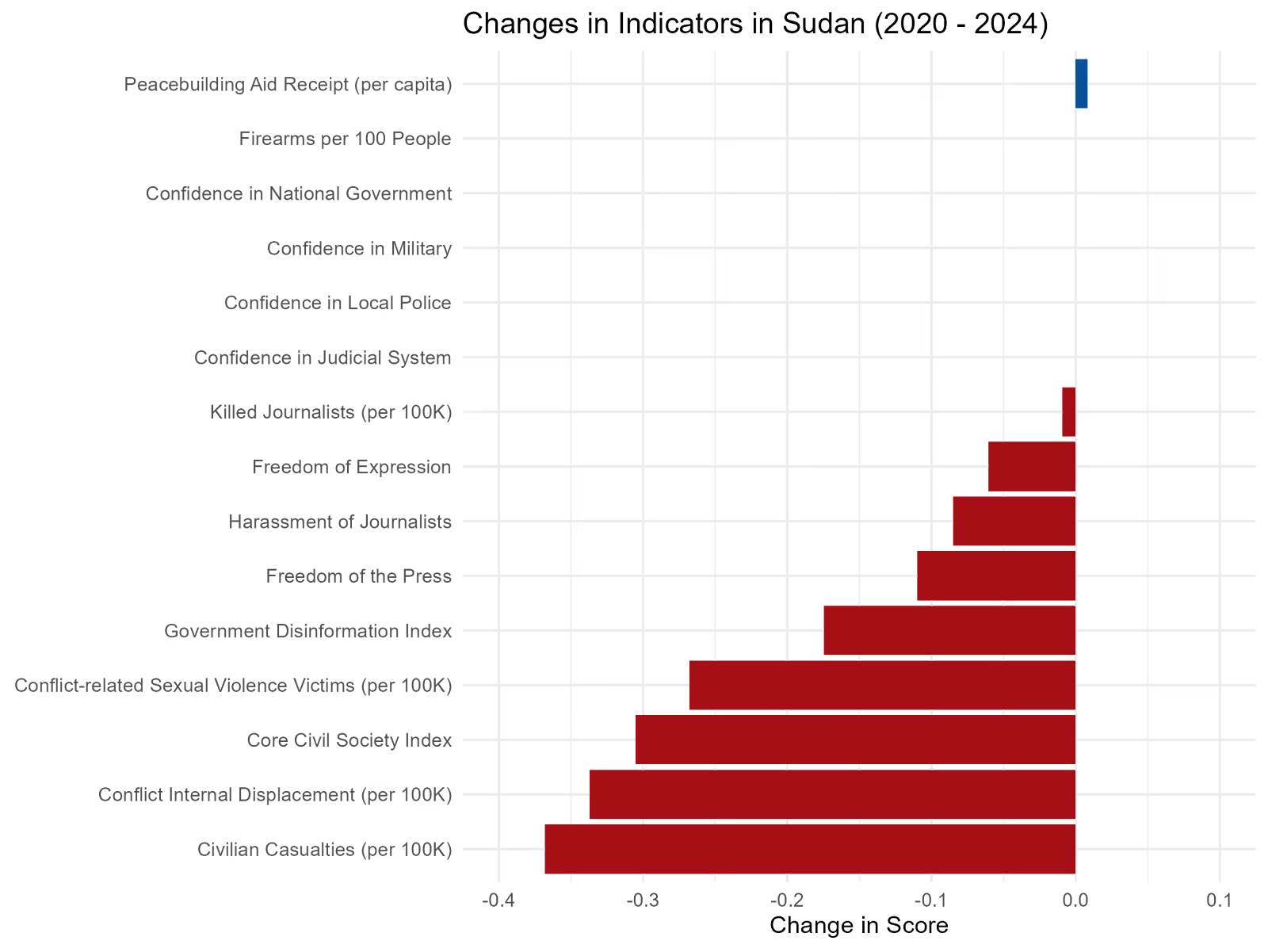

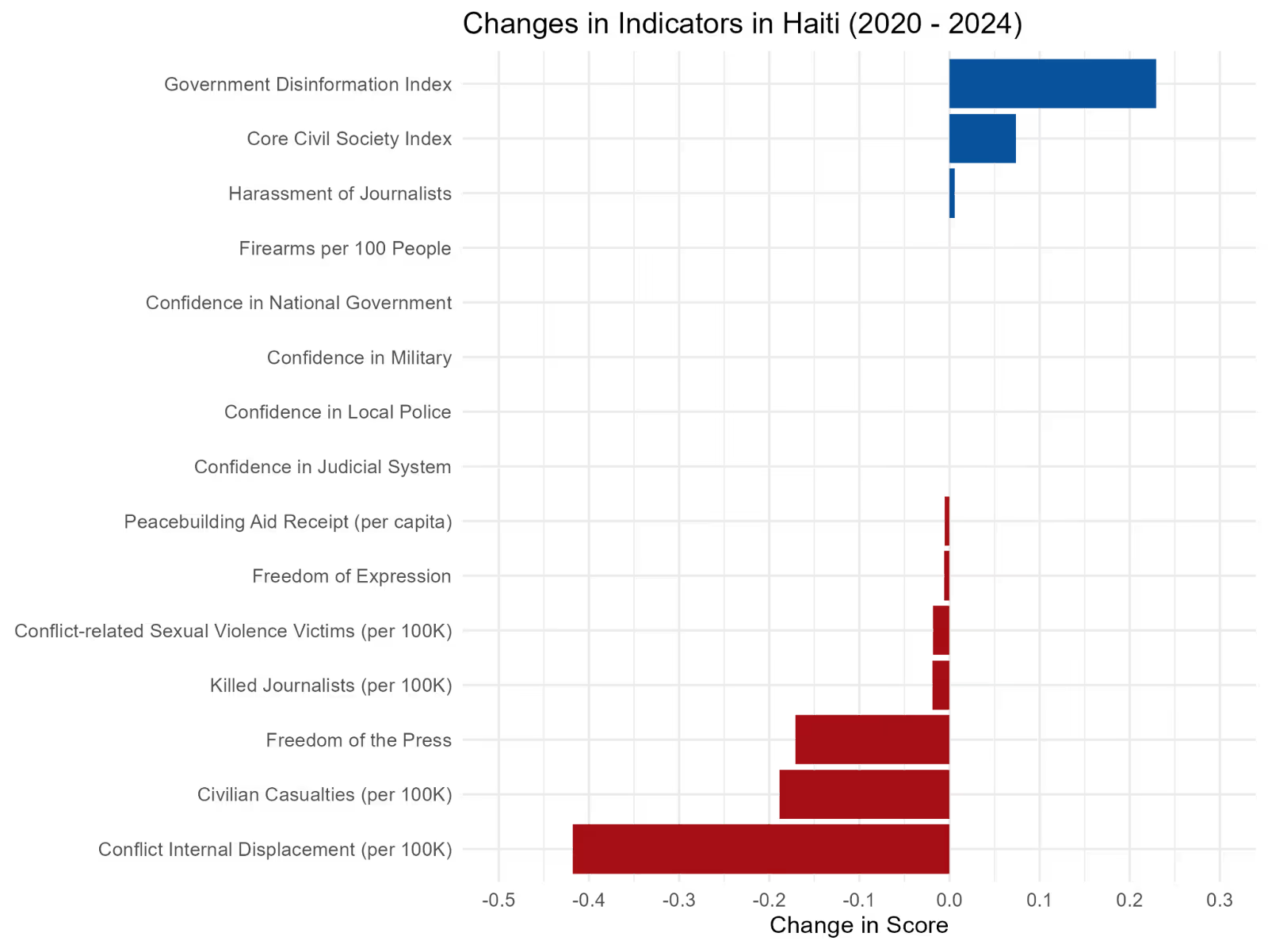

A lack of media coverage does not only reflect global interest but also stems from broader challenges facing the media sector. International outlets have consistently reduced foreign coverage in recent years, leading to a dearth of information from many global conflicts. At the same time, authoritarian regimes are increasingly cracking down on independent media, relying on both legal and bureaucratic harassment, as well as more direct forms of repression such as arbitrary arrests or physical attacks. In the Civilian Protection Index, all three indicators related to the media sector (measuring killed journalists, harassment of journalists, and overall press freedom) declined between 2023 and 2024, with freedom of the press deteriorating more than any other indicator (see also Figure 3 below and Protect: Journalists Under Fire). Similarly, Reporters without Borders in 2024 concluded for the first time that the global media environment had deteriorated to a “problematic” level. This was largely due to the increasing financial crisis facing the sector, coupled with a lack of political will to support independent media.5

Afghanistan exemplifies how a perfect storm of dwindling international interest, a lack of funds, and state repression has eroded a previously vibrant national media scene. Since the Taliban takeover in 2021 and withdrawal of foreign troops, the country has received considerably less international media attention, while most international bureaus in Kabul have closed. Development funding—some of which previously supported independent, national media—has largely been halted by international donors who will not channel resources through the Taliban de facto authorities.6 At the same time, the Taliban has imposed widespread censorship of media, and has tortured, jailed, and killed critical journalists. In the three years since the Taliban takeover, more than half of all Afghan national outlets have been forced to close, while almost all women journalists have lost their jobs.7

Sudan: The World’s Worst Displacement Crisis Remains Overshadowed

Since the outbreak of war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in 2023, Sudan has experienced the worst displacement crisis in the world.8 Levels of civilian casualties and humanitarian needs from the conflict are also both staggering, with more than 30 million people requiring humanitarian assistance in 2024.9 Despite this, Sudan has consistently been eclipsed by other major conflicts in terms of media coverage and donor prioritization, leading both national and international actors to call for it to be higher on the global policy agenda.10 At the beginning of 2024, news coverage of Sudan averaged 600 new articles published per month, while stories on Gaza and Ukraine remained steadily above 100,000.11

A lack of reliable data on casualty figures in Sudan risks obscuring the scale of humanitarian needs, impeding effective aid mobilization, and ultimately undermining civilian protection. Estimates vary considerably, as there is no systemic recording of conflict-related deaths, partly due to a lack of access or resources for international and local monitors. A US diplomat estimated that there had been as many as 150,000 conflict-related deaths already by May 2024.12 Others put the figure even higher. According to the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), 93 percent of all intentional-injury deaths in Khartoum state between April 2023 and June 2024 went unrecorded, meaning that they were absent from three independent data sources used in the study (public survey, private survey, and social media obituaries).13 LSHTM’s study put the death toll due to violence at 26,000 in Khartoum state alone during this time period, compared to ACLED’s estimate of 20,178 intentional-injury deaths across the entire country in the same period. In 2024, 69 percent of the UN’s humanitarian funding request was met by donors.14 While relatively high, this still left millions of people in need without access to aid.

Throughout 2024, civilian protection concerns escalated amid intense violence between the SAF and RSF in the conflict’s epicenter, Khartoum, while fighting also spread to North Darfur and southeastern states. Throughout the year there were also continued air and drone strikes and ground attacks on civilian homes, infrastructure, and healthcare systems, with combatants accused of committing war crimes.15 Rights groups further accused the RSF of crimes against humanity – including murder, torture, rape, and sexual slavery – and other violations of international humanitarian and human rights law.16 In January 2025, the US government concluded that RSF and allied militias had committed violations amounting to genocide in Darfur.17

The violence has sparked the world’s most severe displacement crisis, as 11.5 million people had fled their homes by December 2024.18 According to the IOM, internal displacement rose by 27 percent from the previous year, amounting to a “polycrisis of catastrophic proportions” compounded by violence and climate risks.19 The largest increases in internal displacement were in Gedaref, North Darfur, South Darfur, and River Nile states. By the end of 2024, Sudan hosted 837,966 refugees and asylum seekers, primarily from South Sudan, Eritrea, and Ethiopia; nearly half of whom were in the White Nile state.20 Additionally, over 3.2 million people fled from Sudan to neighboring countries as refugees, mostly to Chad, Egypt, and South Sudan.21 The IOM warned of the deteriorating protection environment facing Sudanese refugees abroad, as civilians faced forced returns from Egypt and rising cases of family separation and trafficking at other border points.22 These displacement dynamics underscore the regional dimensions of Sudan’s protection crisis, which extend beyond the country’s borders.

Conflict-related sexual violence remained a significant source of civilian harm, with millions of women and girls in Sudan facing acute risks. Human Rights Watch documented sexual violence by the SAF during its takeover of Omdurman in 2024.23 At the same time, civilians living under RSF control in Khartoum, Bahri, and Omdurman faced widespread sexual violence, alongside cases of forced and child marriage.24 Although the RSF denies allegations of sexual violence, human rights and civil society organizations have credibly documented sexual violence–including rapes and gang rapes–committed by the RSF against women and girls in Darfur and Gezira State.25 Strategic Initiative for Women in Horn of Africa (SIHA), has accused the group of systematically using sexual violence as an “instrument of war.”26 Harm from sexual violence is compounded because CRSV survivors often lack of access to medical, psychosocial, and legal support following attacks.

Food insecurity rose to catastrophic new heights in 2024. In July, famine was officially declared for the first time since 2020 in North Darfur’s Zamzam camp, which houses hundreds of thousands of IDPs.27 Famine was identified in four more areas of Sudan from October to November, while over half of the country’s population faced acute food insecurity.28

Bureaucratic and administrative impediments, along with other challenges, complicated humanitarian aid delivery and played a critical role in worsening food insecurity and other protection risks. Between January and September, there were 73 reported incidents of humanitarian access impediments across 16 states.29 Local responders, including volunteers and community groups that provide frontline support through Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs), faced continued security challenges. These included targeted attacks, intimidation, sexual violence, and arbitrary detention perpetrated by both warring parties.30 According to the Aid Worker Security Database, 60 aid workers were killed in Sudan in 2024, second only to Gaza globally in terms of the number killed. All of those killed were Sudanese national staff, reflecting the increasing and disproportionate dangers facing local aid actors on the frontlines of conflicts and the urgent need for stronger protection of frontline responders.31

Health services were severely disrupted by targeted attacks and collateral damage, contributing to rising outbreaks of cholera, measles, malaria, and dengue fever. For example, RSF forces attacked the last operating hospital in the Darfur region in June 2024, opening fire inside the hospital, which had already been hit with mortars and bullets on multiple other occasions.32 The World Health Organization reported over 119 attacks on healthcare facilities and workers between the start of the war and October 2024.33 For many displaced people, access to basic medicines and care was increasingly difficult. By November, 80 percent of health facilities in high-intensity conflict zones were non-operational and the rest of Sudan’s health system was “on the brink of collapse.”34 Under these conditions, lack of access to medical care was a widespread challenge for civilians, but was especially acute for displaced persons and survivors of CRSV.

In this dire context, there has been a notable lack of accountability and a diminishing international presence, particularly of UN staff in more remote locations.35 However, in May, the AU Peace and Security Council called for the High-Level Panel on the Resolution of the Conflict in Sudan to work with the AU special envoy for the prevention of genocide, H.E. Adama Dieng, to develop a new POC strategy.36

Funding

Public awareness of a conflict can also impact levels of donor funding to meet civilian needs on the ground. The “Ukraine effect”, for example, led to a significant boost in global humanitarian aid after Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, even as overall funding for other crises dwindled.37 In 2024, donors contributed just over 50 percent of the total $49.4 billion humanitarian actors had requested to meet global needs during the year.38 While this proportion was largely consistent with previous years, the total amount of funding has declined for the past three years ($24.92 billion in 2024; 25.23 billion in 2023; and $30.42 billion in 2022). In 2024, the funding coverage was even lower in several countries that faced high levels of civilian harm from armed conflicts or generalized violence, including Burkina Faso, Haiti (see Spotlight below), Mali, and Myanmar.

Other efforts to evaluate and identify neglected contexts led to similar conclusions. The Humanitarian Funding Forecasts—which tracks how levels of aid meet needs in the longer term—identified several countries with persistently high levels of violence among the most chronically underfunded crises in 2024, including the DRC, South Sudan, Haiti, and Mali.39 Similarly, the Norwegian Refugee Council’s ten most neglected displacement crises in 2024, which considers media attention, funding, and political engagement, included Burkina Faso, the DRC, Mali, and Somalia.40

Haiti: Increasing Violence Triggers Urban Exodus but Limited Protection Response

This article was authored by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC)

The security situation in Haiti reached new lows in 2024, with catastrophic consequences for civilians. A coalition of gangs known as Viv Ansanm carried out a growing number of coordinated attacks throughout the year, bringing much of the country to a standstill for months on end and severely disrupted public services.41 Reports of killings and kidnappings by armed gangs, sexual violence, and devastating food shortages continued unabated.42 Persistent political instability also left a security vacuum.43

Amid ongoing political instability, a new UN-mandated Multinational Security Support (MSS) deployed in 2024 after several delays but was plagued by inadequate financing and ultimately struggled to effectively support the national police in curbing criminal gangs (see Protect section for more details). An effort by some Member States to transform the MSS into a UN peacekeeping mission that could benefit from UN assessed contributions did not achieve consensus in the UN Security Council.44

Haiti’s growing protection crisis has also failed to capture adequate media attention and the country’s humanitarian response plan has been chronically underfunded.45 In 2024, Humanitarian Funding Forecast ranked Haiti as the fourth most chronically under-funded country in the world.46 Haiti’s Humanitarian Response Plan was only funded at 44 percent overall in 2024, with funding for protection activities even lower, at 33.5 percent.47

The escalating violence in Haiti has also caused a displacement crisis, with a record 889,000 movements during the year, leaving over a million people internally displaced as of the end of 2024 – amounting to about nine percent of the population.48 The number of people internally displaced at the end of 2024 was three times higher than in 2023, and six times higher than in 2022. Assaults on government buildings and infrastructure forced some displacement sites to temporarily close, leaving many IDPs without shelter.49

Limited resources, including food, led to mounting tensions between IDPs and host communities, to the extent that 40 percent of the latter reported being unable to continue hosting those displaced, and 15 percent explicitly refused to do so.50 An increasing number of people moved to displacement sites in Port-au-Prince as a result, but overcrowding, deteriorating living conditions, and persistant violence contributed to an urban exodus of IDPs toward other provinces.51 By the end of the year, three-quarters of the country’s IDPs were outside Port-au-Prince, with many lacking access to humanitarian aid or basic services.52

The situation of children, who make up more than half of the country’s IDPs, was particularly alarming. Not only were they deprived of education, but many were also subjected to forced recruitment, a trend that increased by 70 percent in 2024. Some estimates indicate minors make up about half of the gangs’ members.53 Some families separated as a means of shielding children from criminal violence, including by sending their children unaccompanied to other provinces.54 Despite the grave situation facing children, UNICEF’s Humanitarian Action for Children appeal was only 28 percent funded.55

Gender-based violence remained a major issue. Around 1.2 million people in Haiti required protection from gender-based violence in 2024, more than double the figure for the previous year. Gangs continued to use rape and sexual assault as a means to exert control over the population, and targeted displacement sites to restrict access to humanitarian assistance.56 Most people identified as victims of gender-based violence were internally displaced.57 IDPs also faced higher risks of intimate partner violence in overcrowded displacement sites and host families.58

Food security in Haiti also deteriorated. More than 5.4 million people faced acute food insecurity in the second half of 2024. Over 3,000 people, all of them in displacement sites, were experiencing catastrophic, or IPC phase 5 levels of food insecurity, highlighting IDPs’ heightened vulnerability.59 Prices for staple food items rose in areas to which people had fled, while violence and displacement disrupted agricultural production. The situation was further aggravated by gang control of ports, which continued to restrict the availability of imported goods, including food.60

Essential medical supplies were also limited, forcing some hospitals to close and impeding the response to a cholera outbreak that began in late 2022, and which continued to affect IDPs in overcrowded displacement sites with poor sanitation and hygiene conditions in 2024.61

While increased humanitarian aid will help displaced persons meet their most pressing needs in the short term, Haiti’s multi-faceted crisis requires comprehensive action to address the structural and underlying drivers of violence. These include strengthening security, reducing poverty, and tackling inequality. This will require sustained international efforts, including through continued humanitarian and political support. Member states should adequately resource the MSS if it is to effectively support the Haitian National Police in curbing violence, and should regularly re-evaluate whether the MSS in its current form and strength is fit for purpose.

Political Attention

Political engagement is less quantifiable and measurable than media coverage or humanitarian funding. UN-level action, however, is one indicator of the relative political will to address a given conflict. While the UN Security Council held a record number of formal meetings in 2024, its agenda was not always determined by the intensity of a conflict or levels of civilian harm (for more details, see Spotlight: UNSC Report).

The UN General Assembly, although lacking the political influence of the Security Council, is sometimes viewed as a bellwether for global public opinion.62 In 2024, an analysis of speeches by world leaders at UNGA by the International Crisis Group found that the conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine received the most attention, with comfortably more than 100 mentions each. Sudan was the third-most referenced conflict with 65 mentions, possibly reflecting an attempt by the US and some European states to push the conflict up on the agenda ahead of the Assembly. Notably, only a minority of African states mentioned Sudan in their UNGA speeches. Other global conflicts were primarily raised by states from their immediate neighbourhoods: Myanmar was, for example, mostly mentioned by leaders from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, while 22 of 33 states from Latin America referred to the post-election crisis in Venezuela.63

The UNSC Agenda in 2024

This article was authored by Erik Ramberg from Security Council Report

In 2024, the United Nations Security Council was confronted with a world beset by multiple crises with devastating consequences for civilians, including in Gaza, Haiti, Myanmar, Sudan, and Ukraine. While the Council frequently convened to discuss these and other conflict situations, its attention was not entirely responsive to developments on the ground or apportioned based on the severity of protection crises. Rather, the Council’s meeting agenda remained determined by an opaque mixture of formal mandates and informal practices that together comprise the Council’s engagement on thematic and country issues. Once established, these arrangements can be difficult to amend or suspend, gaining their own political or institutional logic that persists irrespective of shifts in conflict dynamics. Moreover, differing strategic interests and diverging world views among the major powers that make up the Security Council restricted its ability to take meaningful action to address the situations on its agenda.

Some statistics provide insight into these dynamics. In 2024, the Council held 305 formal meetings, averaging 25 per month, and 124 informal consultations.64 This was the highest number of formal meetings on record and six times higher than the number held at the end of the Cold War in 1991. At these meetings, the Council considered a total of 45 agenda items: 23 regarding country-specific or regional situations and 22 on thematic issues. Approximately two-thirds of Council meetings (68 percent) concerned the former type.65 The most frequently considered country-specific agenda item was the Israel-Palestine conflict—formally called “The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question” (MEPQ)—which was the subject of 35 formal meetings and 25 informal consultations. The situation in Israel-Palestine was followed by followed by Ukraine (33 meetings and no consultations); Yemen/Red Sea (19 meetings and 11 consultations); Sudan (18 meetings and eight consultations); Syria (17 meetings and eight consultations); and Haiti (12 meetings and four consultations). Additionally, the Council held eight meetings under the thematic “Protection of civilians” agenda item, of which three concerned country-specific situations: two on Gaza and one on Sudan.66

The Council’s meeting patterns are governed by a patchwork of formal mandates, customary practice, and ad hoc sessions. Any Council member may request the latter, which the Council presidency—rotating monthly among members—is generally expected to accommodate. As a result, the body has a relatively high degree of flexibility to address conflict situations as developments arise on the ground. This is evident in the Council’s engagement on Ukraine, for instance, which in 2024 consisted entirely of ad hoc meetings since the polarized political dynamics characterizing the conflict have prevented agreement on any mandated reporting cycles. The Council’s consideration of the MEPQ agenda item illustrates this point as well: 23 of the 35 formal meetings held on that issue last year—about two-thirds—were convened in response to specific ad hoc requests from Council members.

The twelve remaining MEPQ meetings, however, exemplify the political compromises, inherited conventions, and bureaucratic manoeuvres that also determine the allocation of the Council’s attention. These sessions were the Council’s regular monthly meetings on MEPQ, which it has convened since 2002, when Council members reached an informal agreement on the file’s meeting cycle. While initially a straightforward arrangement, it has evolved over the years into a conglomeration of different types of meetings that rotate between: 1) quarterly open debates, a practice Qatar first initiated during its 2006-07 term; 2) quarterly briefings on the implementation of resolution 2334 (2016), half of which are based on a written report in accordance with another informal agreement that Council members reached following the resolution’s adoption; and 3) regular quarterly briefings.

Syria provides another example of the convoluted institutional dynamics impacting Council deliberations. Although members convened more frequently toward the end of last year to discuss the rebel offensive that ultimately ousted the Assad regime, the total number of Syria-related meetings held throughout the entire year remained relatively high primarily because of prior resolutions, which requested two separate monthly briefings on the country: one on the chemical weapons track, mandated by resolution 2118 (2013), and one on the political and humanitarian situations, mandated by resolution 2268 (2016). While Council members reached a “gentlemen’s agreement” in early 2024 to reduce the frequency of the chemical weapons meetings to a quarterly cycle—responding to long-standing complaints from some Council members that developments on the ground did not warrant monthly meetings on that issue—the total number of sessions remained high compared to many other country situations on the Council’s agenda.

If viewed in isolation, the high number of Council meetings held in 2024 might suggest that the body was effectively discharging its mandate to maintain international peace and security. An analysis of Council outcomes tempers this conclusion, however. Notably, there was a decline in the number of resolutions adopted by the Council in 2024, a trend that began in 2021 and has continued: 46 resolutions were adopted in 2024 compared to 50 in 2023, 54 in 2022, and 57 in 2021. Indeed, the number of resolutions passed in 2024 was lower than in any year since the end of the Cold War in 1991 (42). Approximately 65 percent of adopted resolutions had the support of all 15 members, which is comparable to the proportion of unanimous adoptions in recent years, but low when compared to the post-Cold War period between the mid-1990s and the mid-2010s, during which it was not uncommon for over 90 percent of adoptions to be unanimous in any given year. Additionally, seven draft resolutions were vetoed by permanent members in 2024—the highest number since 1986.67

In some key protection crises, it is striking how few meaningful Council outcomes were adopted because of contentious dynamics. With regard to Ukraine and Myanmar, the Council did not adopt any outcomes last year. In Haiti, the Council was unable to agree on converting the under-resourced Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission into a UN peace operation.68 A draft resolution on measures to protect civilians in Sudan was vetoed by Russia. Three draft resolutions on Gaza were also vetoed: one by China and Russia and two by the US.69

Even more concerning than the Council’s low number of adoptions last year was its inaction in the face of increasingly frequent and flagrant violations of the decisions that it did reach. For instance, despite the aforementioned vetoes, the Council was able to adopt a resolution on Sudan (calling for an end to the siege of El-Fasher) and two on Gaza (calling for ceasefires), but all three went unheeded without any further Council action.70 Additionally, although the Council adopted a resolution in May of last year outlining conflict parties’ obligations to protect humanitarian and UN personnel, 2024 became the deadliest year ever recorded for aid workers—primarily due to the war in Gaza—without eliciting any substantive Council reaction against the responsible parties.71 And Russia continued its strikes on Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure, despite previously voting for resolution 2573 (2021), in which the Council unanimously condemned such attacks.72 The fact that these violations were perpetrated or supported by permanent members of the Council further undermined the body’s credibility and legitimacy.

The Council’s record-high frequency of meetings in 2024 likely reflects contemporary expectations for international action in the face of widespread suffering. At the same time, the continued erosion of its ability to adopt or enforce resolutions reveals the dysfunctional political dynamics—indicative of an increasingly multipolar international system in which a Cold War-style of geopolitics is re-emerging—that prevent the Council from taking substantive measures that require unanimity, or at least the assent of veto-wielding permanent members. These two trends may appear contradictory at first glance but are likely related, as the Council’s inability to act decisively has left its convening power as its sole remaining recourse to address a growing number of situations on its agenda. While the overarching political dynamics may be hard to tackle, Council members will need to find ways of reinvigorating their decision-making tools to remain relevant and credible stewards of international peace and security. Otherwise, the Council is at risk of becoming a stage for a distinctly performative brand of diplomacy.

Footnotes

- Ladislaus Ludescher, "Study shows European mainstream media ignore humanitarian crises in the global south", European Journalism Observatory, May 22, 2024, https://en.ejo.ch/ethics-quality/study-shows-european-mainstream-media-ignore-humanitarian-crises-in-the-global-south.

- "Unequal Attention – Why Some Conflicts Make Headlines and Others Don’t," Visions of Humanity, June 27, 2025, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/unequal-attention-why-some-conflicts-make-headlines-and-others-dont/.

- "Ten humanitarian disasters that were barely reported in 2024," CARE, January 15, 2025, https://www.care.org/media-and-press/ten-humanitarian-disasters-that-were-barely-reported-in-2024/.

- "Burkina Faso: Aid from INGOs only reached 1% of civilians in half of the towns under blockade," Norwegian Refugee Council, March 14, 2024, https://www.nrc.no/news/2024/march/burkina-faso-lack-of-access-to-humanitarian-assistance.

- "RSF World Press Freedom Index 2025: economic fragility a leading threat to press freedom," Reporters without Borders, May 14, 2025, https://rsf.org/en/rsf-world-press-freedom-index-2025-economic-fragility-leading-threat-press-freedom?year=2025&data_type=general.

- International Crisis Group, Afghanistan Three Years after the Taliban Takeover, August 14, 2024.

- UNAMA, Media Freedom in Afghanistan, November 2024.

- "Sudan: Famine Confirmed in 10 Areas," World Food Programme USA, accessed September 2, 2025, https://www.wfpusa.org/place/sudan/#:~:text=The%20most%20recent%20conflict%2C%20which,in%20Sudan%20and%20neighboring%20countries.

- UNOCHA, Sudan: Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2025, December 31, 2024.

- See, for example, Janice Gassam Asare, "The War In Sudan That No One Is Talking About," Forbes, March 31, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/janicegassam/2024/03/31/the-war-in-sudan-that-no-one-is-talking-about/; Michael Curtin, "Sudan, the 'Forgotten War'", Stimson Center, February 14, 2024, https://www.stimson.org/2024/sudan-the-forgotten-war/; "Red Cross urges increased support to avert Sudan’s forgotten crisis," Sudan Tribune, April 8, 2024, https://sudantribune.com/article284243/.

- "Sudan: the war the world forgot", The Economist, May 24, 2024. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2024/05/24/sudan-the-war-the-world-forgot

- Eve Sampson, "Disaster by the Numbers: The Crisis in Sudan", New York Times, January 7, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/07/world/africa/sudan-genocide-numbers.html.

- “‘Invisible and severe' death toll of Sudan conflict revealed", London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, November 13, 2024, https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/newsevents/news/2024/invisible-and-severe-death-toll-sudan-conflict-revealed.

- UNOCHA, Sudan Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2024, accessed September 2, 2025.

- Amnesty International, Annual Report 2025: Sudan, April 28, 2025; Human Rights Watch, World Report 2025: Sudan, January 17, 2025. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2025/country-chapters/sudan#9f5023

- "Sudan: UN Fact-Finding Mission outlines extensive human rights violations, international crimes, urges protection of civilians", UN OHCHR, September 6, 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/09/sudan-un-fact-finding-mission-outlines-extensive-human-rights-violations.

- US Department of State, Genocide Determination in Sudan and Imposing Accountability Measures, January 7, 2025.

- IOM, Sudan and Neighbouring Countries: End of Year Report 2024, February 27, 2025.

- Ibid.

- UNHCR, Annual Results Report 2024: Sudan, May 27, 2025.

- Ibid.

- IOM, Sudan and Neighbouring Countries: End of Year Report 2024.

- Human Rights Watch, World Report 2025: Sudan.

- Ibid.

- Amnesty International, Annual Report 2025: Sudan.

- Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa, Gezira State and the Forgotten Atrocities A Report on Conflict-related Sexual Violence, June 2024.

- Global Network Against Food Crises, 2025 Global Report on Food Crises, July 2025.

- "Emergency: Sudan", WFP, accessed September 2, 2025, https://www.wfp.org/emergencies/sudan-emergency

- UNOCHA, Sudan: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (September 2024), October 30, 2024.

- Human Rights Watch, World Report 2025: Sudan.

- "Security incident data: Sudan", Aid Worker Security Database, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://www.aidworkersecurity.org/incidents/search?detail=1&country=SD&sort=asc&order=Year

- ”Sudan’s Paramilitary RSF Targets Last Operating Hospital in Darfur,” Al Jazeera, June 10, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/6/10/sudan-paramilitary-rsf-targets-last-operating-hospital-in-darfur.

- World Health Organisation, Sudan: Health Emergence Situation Report, October 31, 2024.

- "WHO helps meet the health needs of internally displaced persons in Sudan through support to primary health care facilities", November 6, 2024, World Health Organisation, https://www.emro.who.int/sdn/sudan-news/who-helps-meet-the-health-needs-of-internally-displaced-persons-in-sudan-through-support-to-primary-health-care-facilities.html?v=1

- Julie Gregory, "One Year Ago, War Broke Out in Sudan. What Can Be Done to Prioritize Protection of Civilians?", Stimson Center, April 15, 2024. https://www.stimson.org/2024/one-year-ago-war-broke-out-in-sudan-what-can-be-done-to-prioritize-protection-of-civilians/

- "AU: Roll Out Civilian Protection Mission, Ensure Sudan Probe", Human Rights Watch, June 20, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/06/20/au-roll-out-civilian-protection-mission-ensure-sudan-probe

- ALNAP, "The Humanitarian funding landscape" in Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2025, June 16, 2025, https://alnap.org/help-library/resources/global-humanitarian-assistance-gha-report-2025-e-report/the-humanitarian-funding-landscape/

- UN OCHA, “Global Humanitarian Overview (GHO) snapshot for 2024,” accessed on September 2, 2025, https://fts.unocha.org/plans/overview/2024.

- Humanitarian Funding Forecast, Underfunded Crisis Index, November 11, 2024.

- “The world's most neglected displacement crises in 2024,” Norwegian Refugee Council, June, 3, 2025, https://www.nrc.no/feature/2025/the-worlds-most-neglected-displacement-crises-in-2024/.

- ACLED, Viv Ansanm: Living together, fighting united – the alliance reshaping Haiti’s gangland, October 16, 2024.

- “Haiti: Over 5,600 killed in gang violence in 2024, UN figures show”, UN OHCHR, January 7, 2025, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2025/01/haiti-over-5600-killed-gang-violence-2024-un-figures-show

- International Crisis Group, Locked in Transition: Politics and Violence in Haiti, February 19, 2025.

- “Haiti: Briefing and Consultations,” Security Council Report, January, 21, 2025, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2025/01/haiti-briefing-and-consultations-13.php.

- Haiti ranked as the fifth most under-reported conflict situation globally in 2023 according to CIVIC’s Conflict Media Coverage Index.

- Humanitarian Funding Forecast, Underfunded Crisis Index.

- UN OCHA, Haiti Besoins Humanitaire et Plan de Réponse 2024, January 19, 2024.

- Humanitarian Action, Global Humanitarian Overview 2025, December 4, 2024; IOM DTM, Rapport sur la situation de déplacement interne en Haïti, Round 9 (Décembre 2024), January 14, 2025.

- “Haiti faces record displacement amid escalating gang violence,” UN News, June 20, 2024; International Crisis Group, Haiti: A New Government Faces Up to the Gangs, May 23, 2024; ACLED, Gangs Active in Haiti Double Since 2021, March 6, 2024; IOM DTM, Haiti: Updates on displacement following attacks in the municipality of Port-au-Prince, March 2, 2024

- IOM DTM, Displacement dynamics in Haiti: Understanding the relationships between IDPs and their host communities, impact of IDPs' arrival on these communities, the displacement history of IDPs and their return intentions, September 22, 2024; IOM DTM, Report on the internal displacement situation in Haiti: Round 8, September 22, 2024

- IOM DTM, Displacement dynamics in Haiti; IOM DTM, Rapport sur la situation de déplacement interne en Haïti, Round 9 (Décembre 2024).

- IOM DTM, Rapport sur la situation de déplacement interne en Haïti, Round 9 (Décembre 2024); “As violence and hunger persist, Haitians struggle to meet the most basic needs,” CARE International, May 30, 2024; https://care.ca/2024/05/30/as-violence-and-hunger-persist-haitians-struggle-to-meet-the-most-basic-needs/; “Haiti Displacement Triples Surpassing One Million as Humanitarian Crisis Worsens,” IOM, January 15, 2025, https://www.iom.int/news/haiti-displacement-triples-surpassing-one-million-humanitarian-crisis-worsens.

- “Number of children in Haiti recruited by armed groups soars by 70 per cent in one year,” UNICEF, November 24, 2024, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/number-children-haiti-recruited-armed-groups-soars-70-cent-one-year-unicef.

- Ibid; ACAPS, Briefing note: Update on protection risks in Port-au-Prince, March 7, 2024; ACAPS, Haiti: Impact of conflict on children and youth, September 30, 2024

- UNICEF, Haiti Humanitarian Situation Report No. 11 End-of-Year Sitrep, December 2024.

- ACAPS, Briefing note: Update on protection risks in Port-au-Prince; “Haiti: Displaced women face ‘unprecedented’ level of insecurity and sexual violence,” UN News, July 17, 2024, https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/07/1152206; Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, A Critical Moment: Haiti’s Gang Crisis and International Responses, February 2024

- ACAPS, Briefing note: Update on protection risks in Port-au-Prince.

- Ibid; “Haiti: Displaced women face ‘unprecedented’ level of insecurity and sexual violence,” UN News.

- IPC, Analyse de l’insécurité alimentaire aiguë: Août 2024 - Juin 2025, September 30, 2024

- Mercy Corps, Impact of Gang Violence on Food Systems in Haiti, January 6, 2025

- ACAPS, Thematic report: Criminal gang violence in Port-au-Prince, June 6, 2024; ACAPS, Haiti: Impact of conflict on children and youth, September 30, 2024; International Crisis Group, Haiti: A New Government Faces Up to the Gangs, May 23, 2024; Violence and threats by police force MSF to suspend activities in Port-au-Prince metropolitan area, MSF, November 20, 2024, https://www.msf.org/violence-and-threats-police-force-msf-suspend-activities-port-au-prince-metropolitan-area-haiti.

- Richard Gowan, "The United Nations General Assembly’s Place in Crisis Response", Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, Vol.48:2 Summer 2024.

- International Crisis Group, The Conflicts Competing for Attention at the United Nations, October 31, 2024. https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/conflicts-competing-attention-united-nations

- “Highlights of Security Council Practice 2024,” United Nations Security Council, accessed August 30, 2025, https://main.un.org/securitycouncil/en/content/highlights-2024.

- Ibid.

- UN General Assembly, Report of the Security Council for 2024, UN doc. A/79/2

- “In Hindsight: The Security Council in 2024 and Looking Ahead to 2025,” Security Council Report, December 30, 2024, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2025-01/in-hindsight-the-security-council-in-2024-and-looking-ahead-to-2025.php

- “Haiti: Vote to Renew the Authorisation of the Multinational Security Support Mission,” Security Council Report, September 29, 2024, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2024/09/haiti-vote-to-renew-the-authorisation-of-the-multinational-security-support-mission.php

- “The Middle East, Including the Palestinian Question: Vote on a Draft Resolution,” Security Council Report, March 24, 2024, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2024/03/the-middle-east-including-the-palestinian-question-vote-on-a-draft-resolution-4.php

- “Sudan: Vote on a Draft Resolution,” Security Council Report, June 13, 2024, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2024/06/sudan-vote-on-a-draft-resolution-2.php; “The Middle East, Including the Palestinian Question: Yesterday’s Adoption and Today’s Briefing and Consultations,” Security Council Report, March 26, 2024, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2024/03/the-middle-east-including-the-palestinian-question-yesterdays-adoption-and-todays-briefing-and-consultations.php

- “Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict: Vote on a Draft Resolution,” Security Council Report, May 23, 2024, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2024/05/protection-of-civilians-in-armed-conflict-vote-on-a-draft-resolution.php.

- ACLED, Bombing into Submission: Russian Targeting of Civilians and Infrastructure in Ukraine, February 21, 2025.