Protect

The year 2024 was devastating for civilians in the more than 130 armed conflicts fought across the globe.1 The UN recorded more than 36,000 civilian deaths throughout the year, an almost 10 percent increase from the 33,443 deaths recorded in 2023.2 This rise was largely driven by intensifying conflicts in Sudan, Ukraine, and the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza. In many conflict-affected countries, a dramatic increase in the use of explosive weapons drove up casualty figures while also laying waste to critical civilian infrastructure such as hospitals and schools. Children suffered record levels of grave violations in global conflicts, overwhelmingly due to alleged violations by Israeli forces in Gaza. Hunger, food shortages, and even famine became more pronounced in many conflict-affected countries in 2024, with several armed actors accused of using starvation as a deliberate weapon of war.

Civilian Protection Index Data

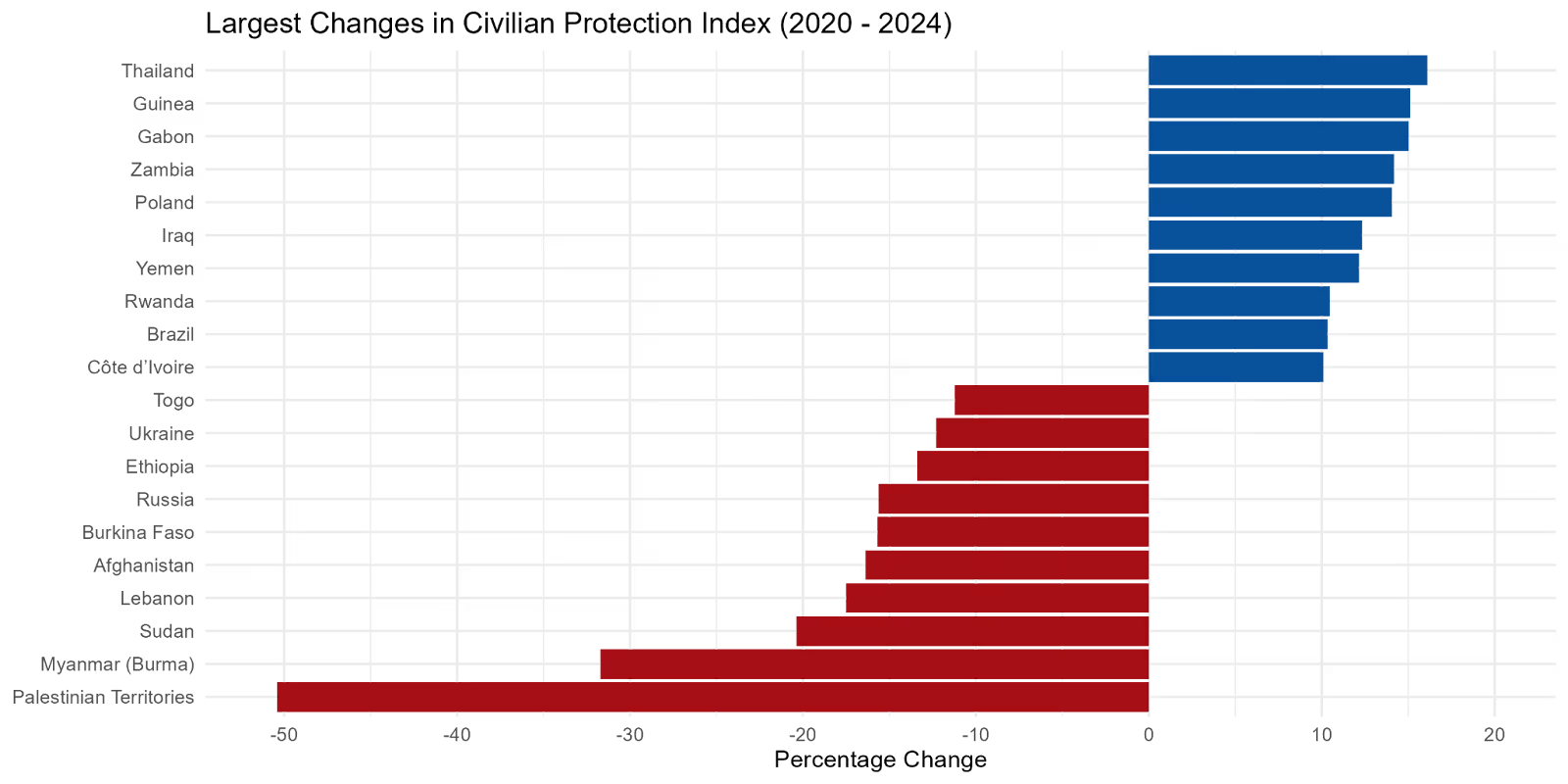

Demonstrating the worsening global conflict situation, CIVIC’s Civilian Protection Index showed that the overall protection environment for civilians deteriorated in 2024 compared to the previous year. In the longer term, civilian protection in conflict has worsened year-on-year since 2020, the first year for which CIVIC has compiled Civilian Protection Index data (see Figure 7). The data revealed that civilians in Afghanistan, Myanmar, North Korea, the oPT, Russia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen faced the weakest protection environments globally in 2024. These were largely the same ten countries that scored the lowest on the Index in 2023, with the exception of Afghanistan, which replaced China. The classification is based on analysis of, not only civilian casualties but also on civilian perceptions of national security and governance institutions as well as government-linked disinformation and civic space. Different issues drove the protection concerns in each of these countries, which can be explored through the interactive Civilian Protection Index map.3 Based on the indicators CIVIC analyzed, civilians in Lithuania, Ireland, Sweden, Senegal, Norway, Finland, Estonia, Denmark, Switzerland, and Timor-Leste enjoyed the strongest civilian protection environment in 2024.4 The inclusion of some countries with mixed human rights records in this category can be at least partially explained by the Index’s reliance on civilian opinion survey data. For these types of data sets, civilians in contexts with lower expectations for government institutions may rate their experiences more positively than those with higher expectations. Additionally, by including an indicator on peacebuilding aid receipt in the Index, the ranking of relatively stable countries that still receive significant peacebuilding aid is elevated.

The countries where the overall protection environment deteriorated the most from 2023 to 2024 were the oPT, Mozambique, Burkina Faso, Lebanon, and Russia, reflecting both intensifying conflict and issues related to governance and civic space. Over the past five years, the oPT and Lebanon were also among the five countries where civilian protection worsened the most, alongside Myanmar, Sudan, and Afghanistan (see Figure 8). More than half of the countries with the worst protection environments were in the sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) regions. In some countries, however, deterioration in protection was balanced by improved perceptions of state institutions’ competence, presenting an overall mixed picture. In MENA, for example, atrocities committed against civilians in the oPT were offset by positive developments in Iraq and Yemen where civilian survey respondents indicated increased confidence in state institutions.

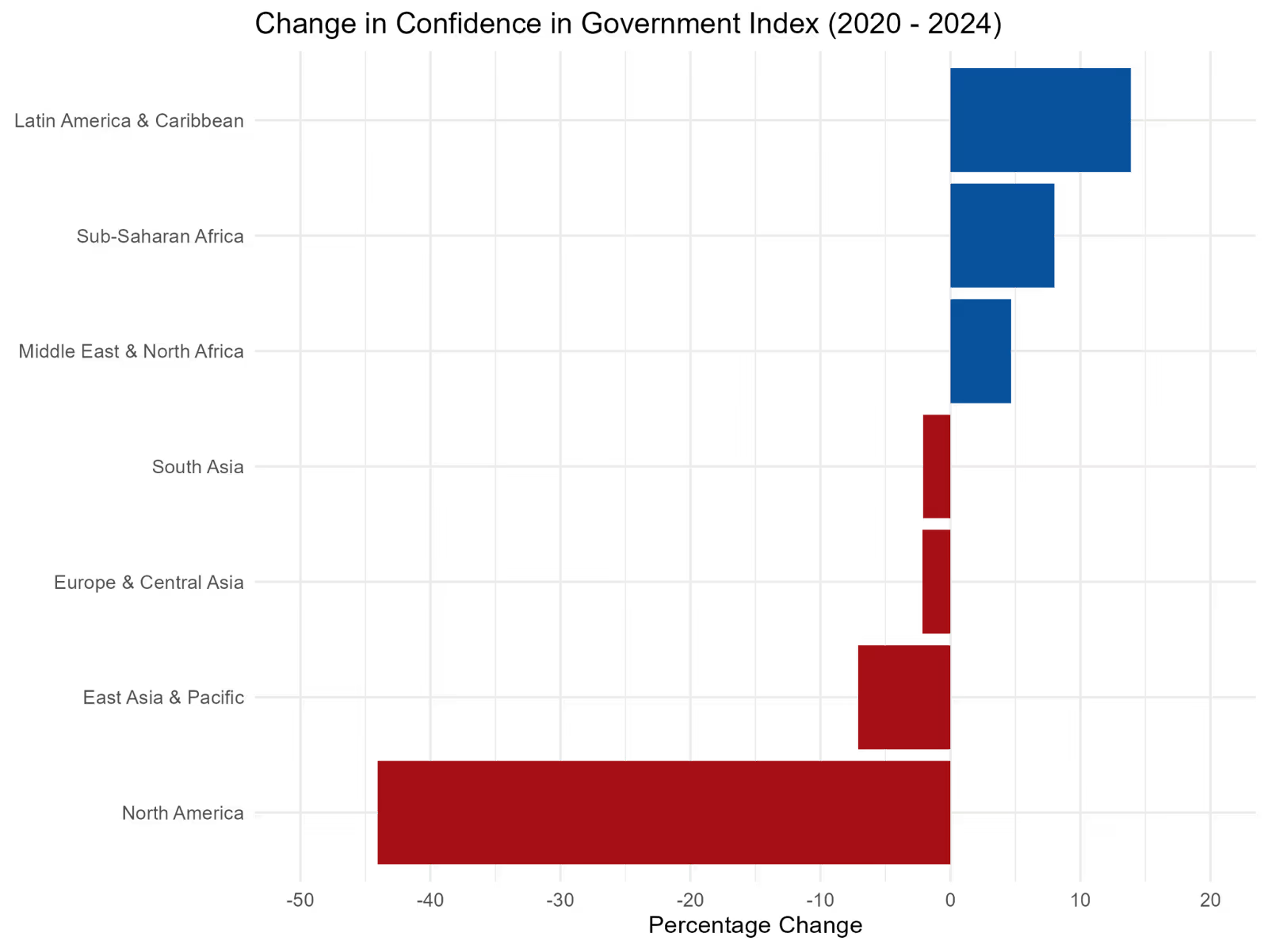

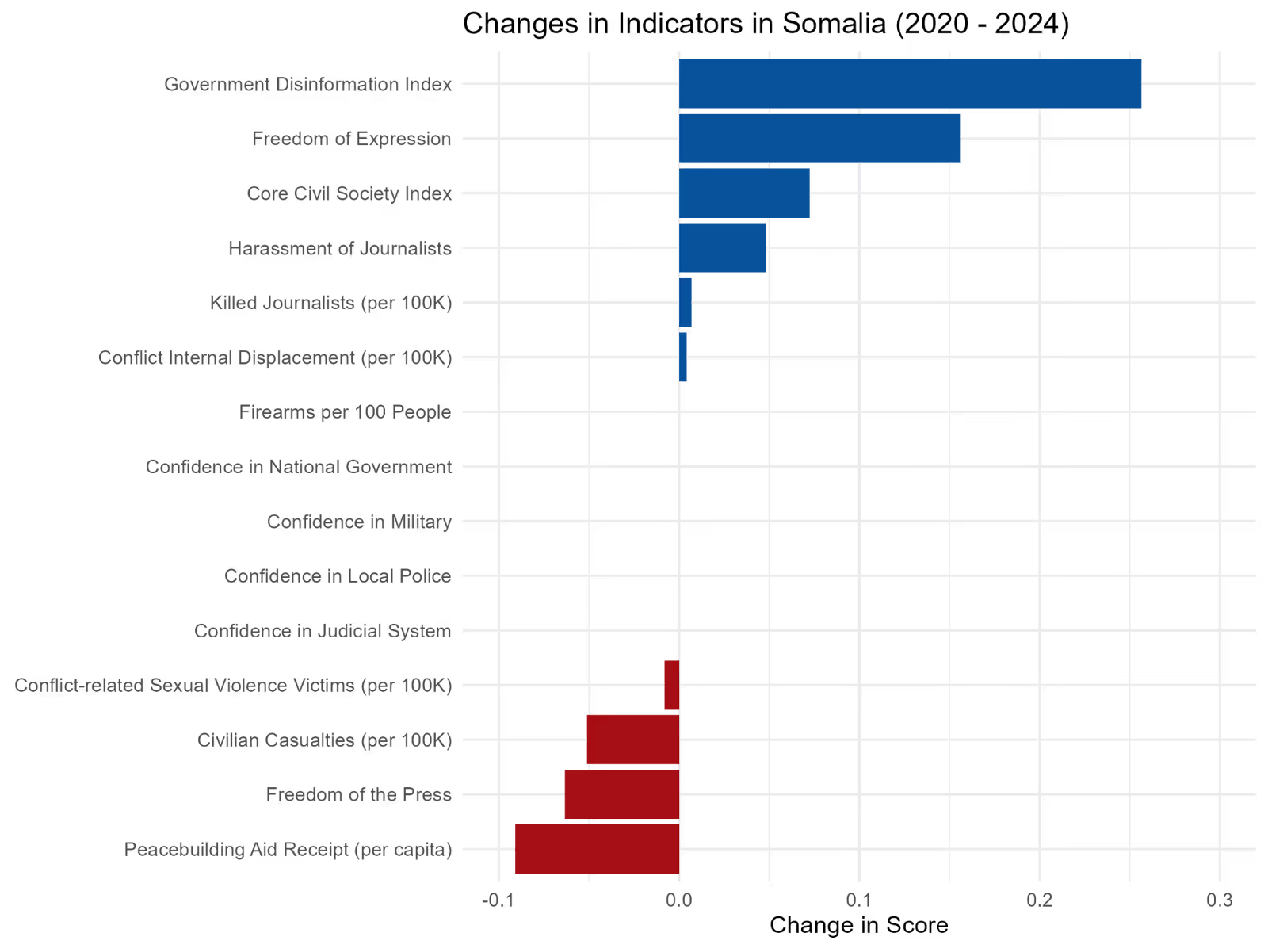

In terms of individual indicators, the Civilian Protection Index noted steep drops in respect for press freedom and civic space last year, as well as in the provision of foreign aid for peacebuilding (see further details below). The latter was a reflection of how several traditional major donors began to reduce foreign aid budgets in 2024—a trend that continued into 2025.5 The biggest positive changes were observed in civilians’ confidence in the four national state institutions covered in the survey: government, judiciary, police, and military. Latin America and the Caribbean saw notable increases in trust in all of these institutions between 2023 and 2024, except for the judiciary, where trust declined. Conversely, the trend was largely negative in North America in both the short (2023 to 2024) and longer (since 2020) terms, with particularly sharp drops in trust in government and the judiciary (Figure 9).6

Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

In 2024, conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) remained widespread and even worsened in many countries, with survivors facing significant barriers to justice.7 The UN verified at least 4,600 cases of sexual violence in conflict across 21 countries in 2024, a staggering 92 percent of which involved women and girls.8 The highest number of recorded cases was in the CAR, the DRC, Haiti, Somalia, and South Sudan. The actual number is likely to be significantly higher, however, as CRSV remains chronically under-reported, often because social stigma means that survivors may face socioeconomic exclusion. According to the Global Protection Cluster, gender-based violence, which includes CRSV, was recorded as “severe” or “extreme” in 88 percent of countries monitored (22 of 25), with the highest levels of risk for people in the oPT, Sudan, Mozambique, Afghanistan, Somalia, Haiti, and Venezuela.9 Similarly, the Civilian Protection Index noted an overall worsening trend for CRSV globally, while the oPT, Sudan, Burundi, Papua New Guinea, and the CAR were the countries where civilians were most at risk of CRSV in 2024. In addition, there were notable deteriorations in the oPT and Burundi from the previous year.

The 2024 Annual Report of the Secretary-General on Conflict-Related Sexual Violence highlighted a number of emerging and entrenched trends. Displaced women and girls continued to face heightened risks of sexual violence, while reports of sexual violence against women in the course of essential livelihood activities remained high. The report highlighted such violations against women in the DRC while they were searching for food or water, in particular.10 More than 70 percent of actors listed in the Secretary-General’s report are persistent perpetrators, appearing in the annex for five years or more without taking corrective action.11 Acknowledging the need for sanctions committees to more consistently address such persistent perpetrators, the Security Council explicitly recognized sexual and gender-based violence as sanctionable in relation to ISIL (Da’esh), al-Qaeda, and associated actors through Resolution 2734(2024), passed in June.12

The often-neglected issue of reproductive violence in conflict also came into stark focus in 2024, driven by developments in the oPT, Ukraine, Sudan, and elsewhere. Reproductive violence is a distinct form of GBV targeting reproductive autonomy, which includes, but is not limited to, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, forced abortion, forced contraceptive use, restrictions on access to reproductive care, and the destruction of essential reproductive healthcare infrastructure.13 The UN documented Israeli Security Forces deliberately attacking sexual and reproductive healthcare facilities in Gaza in 2024, while Russia reportedly bombed maternity wards in Ukraine and forcibly sterilized Ukrainian men and women in captivity.14 In Sudan, the UN further highlighted how violent rapes impacted the reproductive health of survivors, including through gynaecological or urinary infections, painful menstruation, and miscarriages.15

Violence Against Children

In 2024, for the second year in a row, violence against children in conflict-affected countries reached unprecedented levels. The UN recorded 41,370 grave violations against children during the year (5,149 of which had been committed the previous year but were verified in 2024), a concerning 25 percent increase from 2023, and the highest number of grave violations ever recorded.16 This included 4,676 killings of children and, notably, verified cases of rape or other sexual violence against children rose by 25 percent compared to 2023. The UN recorded a nearly five-fold increase in grave violations in Haiti, leading the Secretary-General to add the Viv Ansanm coalition of armed gangs to his annexed list of perpetrators, the so-called “list of shame.” Armed groups from the CAR, Colombia, the DRC, and Sudan were also added for the first time. Israel and the oPT remained the context with the highest number of grave violations for the second year in a row, followed by the DRC, Somalia, and Nigeria. Both Israeli security forces and Palestinian armed groups remained on the “list of shame,” having been added for the first time in 2023. While the list of perpetrators has often served as an effective pressure tool, human rights groups raised concerns that some actors responsible for grave violations continue to be omitted, as well the Secretary-General’s decision to delist groups from Iraq and the Philippines in 2024 without explanation.17

Rising Al-Shabaab Violence in Somalia’s Lower Juba Following Government Offensive

Somalia continued to experience intense battles between government forces and the armed non-state actor al-Shabaab in 2024, although ACLED data showed a decrease in civilian fatalities and injuries perpetrated by al-Shabaab compared to 2023.18 These clashes had a devastating impact on civilian lives and property, displacing thousands in affected areas. In one deadly assault against a beach hotel on August 2, al-Shabaab killed at least 37 civilians and injured more than 200 others.19

Compared to the rest of the country, the Lower Juba region experienced a sharp rise in violence in 2024, with increased attacks against civilians.20 This escalation followed operations launched in early 2024 by Somali National Army (SNA) and Darawish Jubaland forces in Kismayo and its surrounding areas. The military campaign aimed to reclaim al-Shabaab-held territory and stabilize Kismayo and the corridor between Kismayo and Afmadow, a critical supply and movement corridor. Another key military objective was to reopen major supply lines linking the three main Jubaland-controlled towns of Kismayo, Afmadow, and Dhobley.

The joint SNA and Darawish operations from March to July 2024, succeeded in pushing al-Shabaab out of several strategic towns and villages around Kismayo. However, in retaliation, al-Shabaab launched a coordinated, multi-pronged offensive in July 2024, targeting SNA and Darawish bases in the recovered areas of Bulo-Haji and the towns of Harbole, Miido, and Bar Sanguni.21 These military operations and the resulting al-Shabaab counterattacks inflicted heavy costs on civilians. Communities suffered significant loss of life, destruction of property, restricted humanitarian access, and mass displacement.22 Al-Shabaab also reportedly increased violence and targeting of civilians, accusing them of collaborating with government security forces.23 This civilian harm fits a pattern that is all too common in war—militaries retake but cannot protect or hold recovered territory, exposing civilians to retaliation from non-state armed groups and leaving a wake of destruction.

Civilians fleeing frontline hostilities were also displaced by the violence. According to UNHCR’s Protection and Solutions Monitoring Network (PSMN), approximately 570 households, comprising 3,420 individuals, were displaced to Afmadow and Kismayo.24 The Jubaland Commission for Refugees and IDPs (JUCRI) reported even higher figures, estimating 828 households (4,968 individuals) were displaced.25 Civilians displaced by the military operations either joined existing IDP camps or established new settlements, worsening an already dire humanitarian situation marked by high internal displacement and dwindling humanitarian aid.

Attacks on Healthcare and Education

Attacks on healthcare escalated in 2024. The Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition (SHCC) recorded 3,623 such incidents, a 15 percent increase from the previous year, largely driven by intensifying conflicts in Lebanon, the oPT, Myanmar, Sudan, and Ukraine. Violent incidents that damaged or destroyed health facilities more than doubled compared to 2023, while over 900 healthcare workers were killed, the highest number since SHCC began recording data.26 Attacks on schools similarly continued to characterize many global conflicts, despite being explicitly prohibited under IHL in all but exceptional circumstances. In Gaza, 88 percent of all school buildings (496 out of 564) were in need of reconstruction by the end of the year, while all children missed out on the academic year.27 In Ukraine, attacks on education more than doubled from 2023 to 2024, with at least 576 educational facilities damaged or destroyed during the year.28 One country, Rwanda, signed the Safe Schools Declaration (SSD) in 2024, bringing the total number of signatories to 120 by year’s end.29

Displacement

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) provided data and analysis for this section

A record 123.2 million people were displaced by the end of 2024, an increase of seven million people, or six percent, compared to the end of 2023. The vast majority (73.5 million) were displaced within their own countries—the highest number of IDPs ever recorded and representing an increase of 6.5 million from 2023. More than a third of those displaced came from just four countries: Sudan (14.3 million), Syria (13.5 million), Afghanistan (10.3 million), and Ukraine (8.8 million). Ongoing conflict also triggered significant displacements in other contexts during 2024, including in Myanmar, the oPT, the DRC, and the central Sahel, while rampant gang violence in Haiti led to internal displacement tripling to more than one million people by the end of the year. As in 2023, 40 percent of all displaced people globally were children.30 Climate change continued to exacerbate the impacts of conflict, forcing people to flee their homes, with approximately 9.8 million internally displaced by disasters at the end of 2024 (see Spotlight: When Guns, Disasters, and Displacement Meet in the Prevent section of this report for further details).31

People living in situations of displacement are often forced to move multiple times. This happened frequently in Gaza, where, by the start of 2024, 90 percent of people had already been uprooted. Other examples include the DRC and Sudan, which together accounted for nearly half of the 20.1 million movements associated with conflict and violence globally in 2024. Such repeated displacement heightens IDPs’ needs and vulnerabilities and fuels protracted crises.

Refugee and IDP returns rose by 60 percent in 2024 compared to 2023. The 1.6 million refugee returns recorded in 2024 was the highest figure in more than two decades, although many returned to fragile situations where the risk of continued rights violations remained high.32 Both Pakistani and Iranian authorities were accused of illegally coercing more than 1.5 million Afghans (living as refugees or in refugee-like situations) to return to a country where they are at risk of pervasive poverty, persecution, or other abuses, particularly as the Taliban de facto authorities imposed unprecedented restrictions on almost all aspects of life for women and girls.33

Conflict and Hunger

Hunger, including famine, became an even more defining feature of conflict in 2024. Almost two-thirds (65 percent) of the 44.4 million people facing acute food insecurity lived in conflict-affected areas, while 1.9 million people were on the brink of famine by the end of the year, mainly in Gaza and Sudan.34 The UN and others raised warnings about warring parties using starvation as a method of warfare in various countries, including Sudan, the oPT, and Myanmar.35 In November, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants against two senior Israeli officials, including Prime Minister Netanyahu, for crimes including deliberate starvation as a war crime, the first time in the Court’s history this crime had been explicitly invoked.36 While legal analysts have raised questions about the multi-faceted difficulties in ultimately proving starvation crimes, the ICC warrants reflect a greater awareness of the need for accountability on the issue, building on the landmark UNSC Resolution 2417 (2018).37

Explosive Weapons

Explosive weapons continued to take a devastating toll on civilians in conflict-affected contexts, with global civilian deaths from such weapons increasing by more than half in 2024 as compared to 2023, most notably in Lebanon, Myanmar, Syria, and Ukraine (for more information, see Spotlight: Counting the Blasts). In total, 88 states have now endorsed the EWIPA political declaration, an increase from 83 when it was first adopted in 2022.38 In April, representatives from more than 90 countries gathered in Norway for the first-ever follow-up conference on the EWIPA political declaration, resulting in an outcome statement emphasizing the need to better implement the declaration at a national level through legal and policy changes.39 Five of the endorsing states, however, were allegedly responsible for harming civilians in attacks using explosive weapons in 2024: Jordan, Somalia, Togo, Türkiye, and the United States.40

Moreover, there were signs of waning political support for other key international norms and agreements to limit the impact of explosive weapons, including the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Iran, North Korea, and South Korea increased production of cluster munitions. Additionally, the US transferred cluster munitions to Ukraine several times in 2024 and also approved the transfer of anti-personnel landmines, with widespread support for this move among European countries despite data demonstrating the outsized harm civilians suffer from such munitions. For instance, the Cluster Munition Coalition recorded 314 casualties from cluster munitions in 2024, none of which were combatants. All of these casualties were civilians and 42 percent were children. Most (193 casualties) took place in Ukraine.41

Counting the Blasts: The Civilian Burden of Explosive Weapons in an Unrelenting Year

This article was authored by Iain Overton and Niamh Gillen from Action on Armed Violence (AOAV)

The use of explosive weapons in conflict has continued to rise, with civilians once again bearing the overwhelming burden. In 2024, Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) recorded 67,026 casualties from explosive weapons across 9,553 incidents worldwide. Of those harmed, 59,524 were civilians. This figure marks the highest annual total of civilian casualties in AOAV’s records since systematic monitoring began in 2010.

It must be stressed, however, that these figures are drawn exclusively from English-language media reports. They represent only a fraction of the true toll. Many regions suffer from limited press access, censorship, or reporting fatigue that leads to unreported or undercounted on incidents. This is especially true for conflicts where international media presence is weak or restricted and in areas experiencing sustained bombardment, such as Gaza. The data should therefore be seen, not as comprehensive casualty totals. Still, the data reveal clear and consistent patterns of harm. AOAV’s methodology does not aim to capture every death or injury, but to highlight the recurrent and preventable civilian impact of explosive violence.

The horrors of such patterns cannot be denied. In populated areas, 95 percent of those killed or injured by explosive weapons in 2024 were civilians. This reflects a trend AOAV has observed for over a decade: over this longer time period, when these weapons are used in towns, cities, or encampments, nine out of ten casualties are non-combatants.

Nowhere was this harm more evident than in Gaza. In 2024, AOAV recorded 23,432 civilian casualties in the enclave, including 14,145 fatalities. This figure represents 39 percent of all civilian harm from explosive weapons globally last year. Again, these numbers are drawn from English-language media and are likely to represent a significant undercount of the real toll. AOAV’s research suggests that as much as two-thirds of deaths in Gaza are not captured by such reporting. Nonetheless, the data point to a sustained and disproportionate pattern of violence against civilians. Almost all recorded incidents in Gaza took place in populated areas, and 99.9 percent of civilian casualties were attributed to Israeli state forces.

Beyond Gaza, Lebanon experienced a dramatic escalation. Civilian casualties there surged by more than 6,000 percent, from 141 in 2023 to 9,100 in 2024. A large part of this increase was driven by Israeli use of explosive devices disguised as pagers and radios in densely populated areas of Beirut and southern Lebanon. These attacks represent one of the deadliest uses of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) by a state actor in AOAV’s dataset.

Ukraine continued to face high levels of civilian harm. AOAV recorded 11,765 civilian casualties there, making it the second most affected country after Gaza. Nearly all of these casualties occurred in populated areas. Although air strikes rose significantly, the majority of civilian harm was still caused by ground-launched weapons, which tend to be indiscriminate in their effect. In Sudan, where the civil war deepened, AOAV recorded 4,478 civilian casualties. This marks the highest total in Sudan since AOAV began recording, with many attacks targeting residential areas, markets, and encampments.

In Myanmar, explosive violence killed or injured 3,379 civilians, a 56 percent increase from 2023. Most of this harm was caused by the military junta’s aerial bombardments. These attacks tended to hit urban areas and often targeted infrastructure vital to civilian life. In Iran, a single suicide bombing at a public gathering caused hundreds of casualties, contributing to a recorded 8,320 percent rise in civilian harm from explosive weapons in that country.

AOAV’s data reveal, not just the scale, but the nature of explosive violence in 2024. Of the 9,553 recorded incidents, 86 percent occurred in populated areas, while 97 percent of the casualties from these incidents were in populated areas. Residential zones, schools, camps for the displaced, and urban marketplaces were frequently targeted. In total, 8,204 such incidents were recorded in populated settings, causing the deaths or injuries of 57,506 civilians.

In 2024, explosive violence was dominated by state actors: states were the reported perpetrators of 7,999 incidents, which resulted in 56,465 total casualties across 28 countries. Of these casualties, 93 percent (52,259) were reported as civilians. Israel was the predominant state perpetrator of civilian harm, accounting for 33,372 civilian casualties, which is 55 percent of all the civilian casualties recorded globally in 2024. These civilian casualties were recorded across seven states and territories, but 70 percent (23,425) of the civilian casualties caused by Israel took place in Gaza.

In the first five months of 2025 (January to May), AOAV has recorded 3,371 incidents of explosive violence, resulting in 18,999 civilian casualties (7,869 killed). Gaza remains the worst impacted, with 31 percent (5,937) civilian casualties recorded, followed by Ukraine where 28 percent (5,363) of civilian casualties were recorded. This is a similar level of harm in comparison to the same time period in 2024, but with levels of civilian harm showing little sign of reducing in the near future, it can be expected that these figures could surpass the levels seen in 2024.

Our evidence points to an overwhelming truth. Civilians are consistently and disproportionately affected when explosive weapons are used in populated areas. Despite the adoption of the 2022 Political Declaration on Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas, little has changed on the ground. State and non-state actors continue to use wide-area effect weapons in locations where civilians live, work, and seek refuge.

This report is not a complete ledger of loss. But it does serve as a warning as to what happens when war is fought in streets, shelters, and homes. And it calls on those with power and responsibility to change course from such behavior.

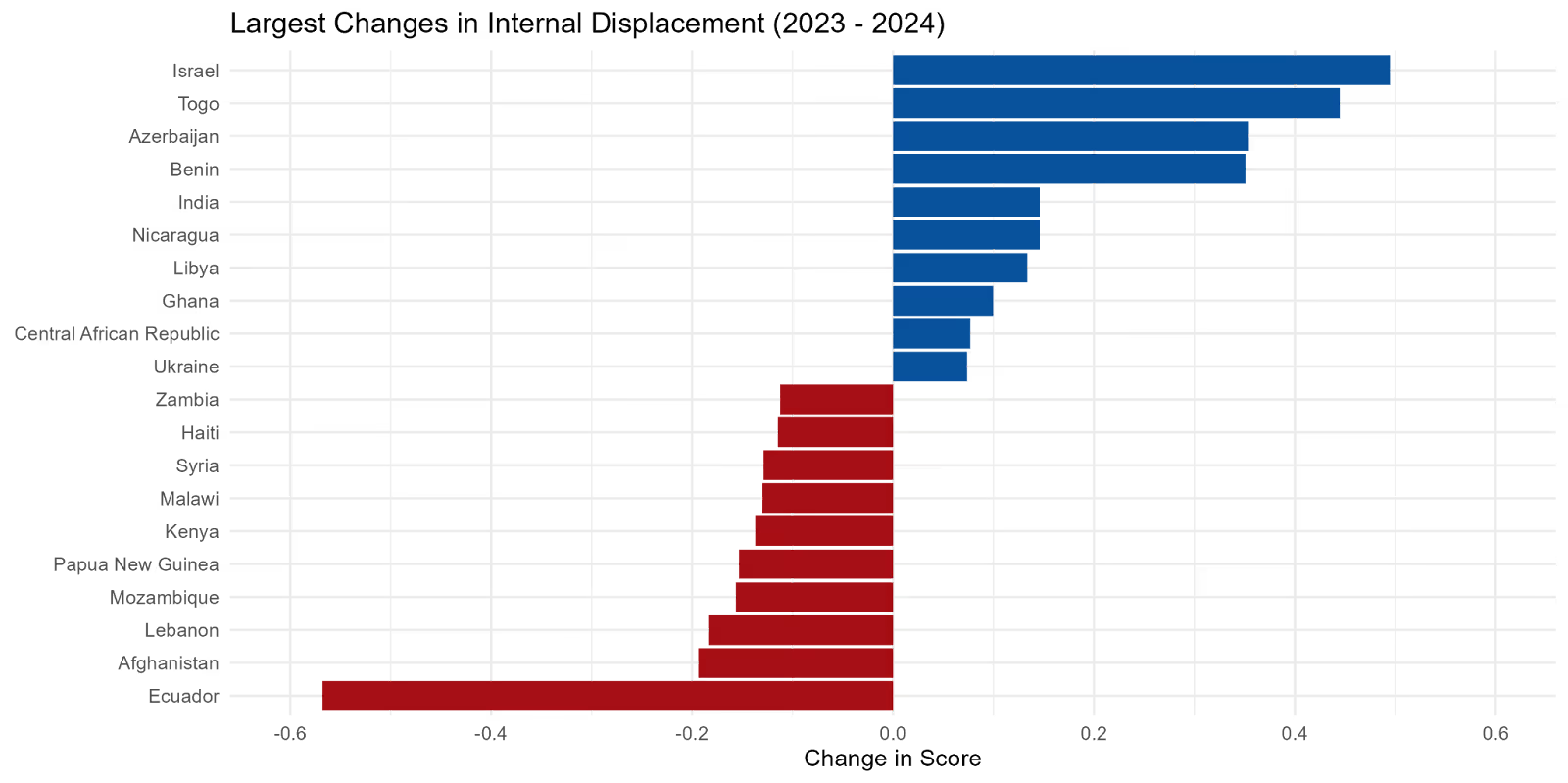

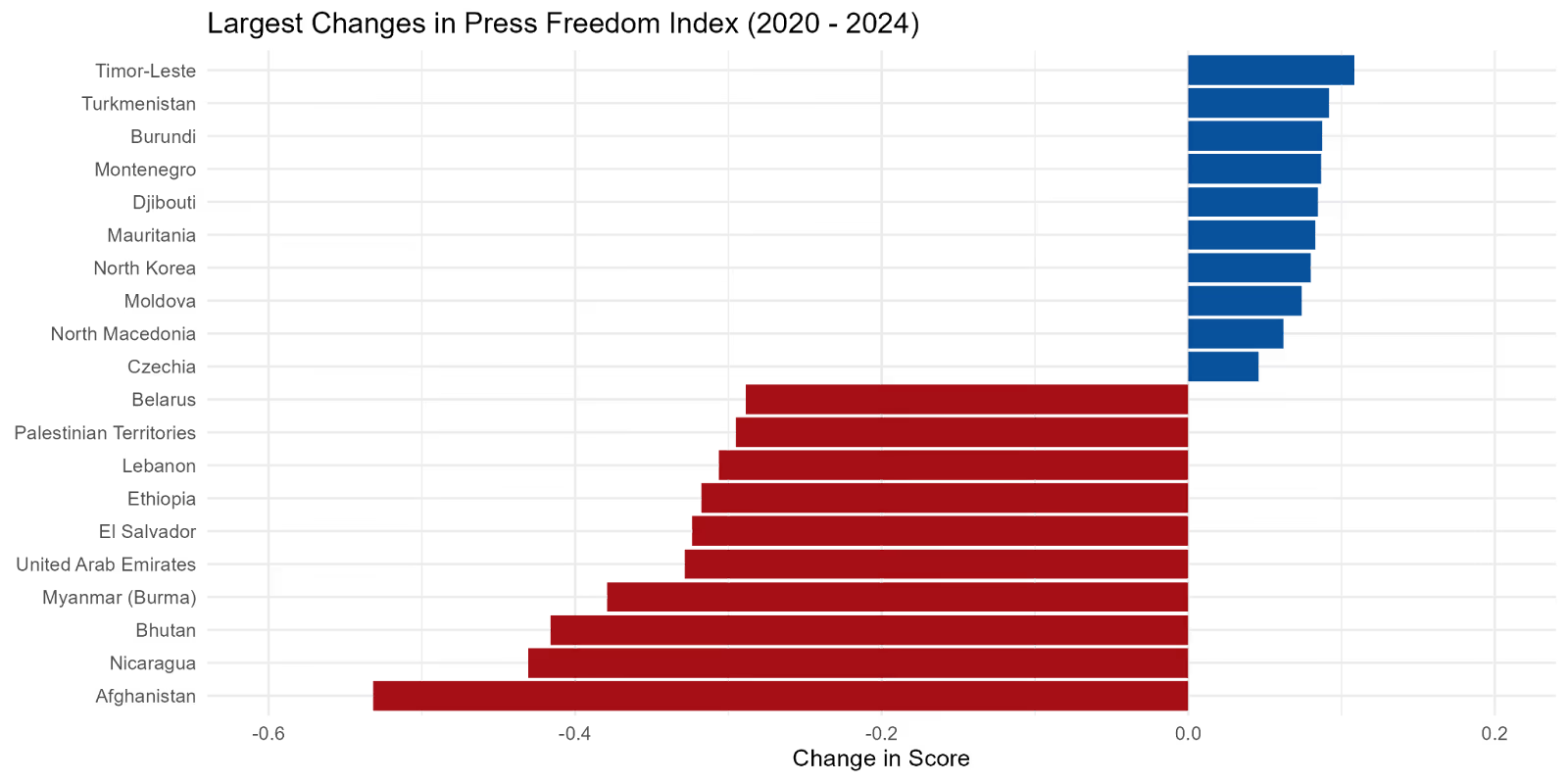

Journalism Under Fire

For media workers in conflict zones, 2024 was a particularly deadly year. According to UNESCO, more than 60 percent (54 out of 82) of journalists killed in 2024 were killed countries experiencing conflict, the highest proportion in more than a decade.42 The year also marked a sharp rise in both proportion and absolute numbers from 2023, when 35 of 71 journalists killed were in conflict contexts. Although media watchdogs rely on different methodologies for tallying attacks on media workers, there is consensus that the oPT remained by far the deadliest conflict for the media in 2024.43 According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Israeli forces killed 85 media workers in Gaza and Lebanon during the year, including ten deliberately targeted because of their work.44 These overall trends were reflected in CIVIC’s Civilian Protection Index, where all three indicators related to freedom of expression and the media declined from 2023 to 2024. The Freedom of the Press indicator, which relies on data from the NGO Reporters Without Borders, saw a sharper drop than any other indicator measured in the Index, with a reduction of more than six percent from 2023 to 2024, and almost 20 percent since 2020. Apart from the oPT, there were also marked deteriorations of press freedom in other countries such as Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Bhutan, and Myanmar, as shown in the graph below (Figure 12).

Military Spending

World military spending rose to more than $2.7 trillion in 2024, marking a decade of year-on-year increases in spending, rising 37 percent from 2015 to 2024. The 9.4 percent increase from 2023 to 2024 marked the highest year-on-year rise since at least the end of the Cold War. Average military spending as a share of government expenditure also rose to a global average of 7.1 percent. The US’s share of world military spending (37 percent) continued to dwarf that of other countries. Of the world’s top 15 military spenders, Russia (+38 percent) and Israel (+65 percent) saw the largest increases in 2024, reflecting spending driven by the major conflicts to which these states are party. As in 2023, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute noted increases in military spending in all five regions it tracks. Europe, however, saw the largest increase in 2024 as spending rose by 17 percent to $693 billion. While $149 billion of this was attributed to Russia, several Western European countries also saw unprecedented rises in military expenditure during the year, notably Germany and Poland.45

The Institute for Economics and Peace has further noted that the nature of military spending has shifted. Despite an increase in overall expenditure, the total number of military personnel globally has steadily declined. Instead, investment is shifting to more capital intensive, technologically advanced armed forces. These include investments in AI, autonomous weapons systems, cyber warfare, and sophisticated missile technology, all of which present new challenges for the protection of civilians in conflict (see Prevent). This rise in spending has not been accompanied by similar investments in peacebuilding: in 2024, expenditure on peacebuilding and peacekeeping was just 0.52 percent of total military spending, compared to 0.83 percent ten years ago.46

Responding to Protection Threats: Aid Workers Under Attack, Increasing Humanitarian Access Challenges, and Shrinking Civic Space

Escalating global conflict led to an increasingly precarious environment for humanitarian aid workers in 2024, both in terms of physical security and operational challenges. Last year was the deadliest year on record for humanitarian personnel, with 383 aid workers killed and 308 wounded, compared to 293 killed and 209 wounded in 2023, according to the Aid Worker Security Database. After a drop in 2023, kidnappings of aid workers also rose in 2024 to 125. More than half (181) of the killings of humanitarian personnel took place in Gaza alone, while Sudan (60) and Nigeria (12) also saw spikes in humanitarian aid worker deaths.

Almost 97 percent (371) of the aid workers killed were nationally recruited, reflecting the extreme dangers facing local and national NGOs (LNNGOs) and other frontline responders who are increasingly assuming primary responsibility for aid delivery in conflict zones.47 The UN Security Council adopted resolution 2730 (2024) calling for better protections for humanitarian workers, while emphasizing the increasing risk facing locally and nationally recruited staff.48 In November, the Secretary-General issued recommendations to Member States on better ensuring the safety of humanitarian personnel in conflict, stressing the need to embed safety considerations in UN mandates and to ensure accountability for attacks.49

Deteriorating security in the context of humanitarian interventions also meant that access challenges increased across the globe. According to ACAPS's Humanitarian Access Index, 35 crisis-affected countries faced “high” to “extreme” levels of humanitarian access challenges by the end of 2024, with the situation deteriorating during the year in 20 percent of countries. This was largely due to the challenges posed by armed conflict to humanitarian personnel, assets, and operations, but also due to factors such as bureaucratic or administrative constraints and the impact of extreme weather events.50 Similarly, in his annual report on children and armed conflict, the Secretary-General noted that denial of humanitarian access to children had reached an “alarming scale” in 2024, leaving girls and boys without access to healthcare, education, protection, and life-saving necessities. The UN recorded 7,906 such incidents in 2024, with Israel responsible for the overwhelming majority (5,091), followed by armed actors operating in Afghanistan, Haiti, and Ukraine.51

Civil society actors also faced a challenging environment for responding to protection concerns. According to the CIVICUS Monitor, civic space continued to shrink globally during the year, with civil society in 81 of 198 countries rated as either “repressed” or “closed.”52 New research from the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of assembly highlighted how hostile and stigmatizing rhetoric increasingly put civil society actors at risk, including in conflict areas where activists are often falsely accused of supporting armed groups to justify repression against them.53

Foreign aid to conflict-affected countries declined significantly in 2024, foreshadowing the even more dramatic cuts many governments have enacted in 2025. Global humanitarian funding (including by government and private actors) in 2024 dropped by 11 percent from the previous year to a total of $41 billion, the largest drop ever recorded.54 Almost all major humanitarian donors reduced aid levels in 2024, with the largest cuts from the US (−$1.7 billion; −10 percent), Germany (−$0.8 billion; −23 percent), and EU institutions (− $426 million, −13 percent). In many ways, this reflected the end of the “Ukraine effect,” which had significantly boosted humanitarian funding since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. In humanitarian settings, protection saw the second-highest cuts in funding of any sector, shrinking by more than one-quarter from $2.437 billion in 2023 to $1.776 billion last year.55 The Global Protection Cluster warned that the sector faced a shortfall of 51 percent compared to what was required to meet the protection needs of 229 million people worldwide. Beyond funding for emergencies, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development reported that official development assistance fell by 7.1 percent in 2024, the first such reduction in five years. This drop was partly driven by reduced funding to Ukraine.56 Similarly, the Civilian Protection Index has shown a steady decline in total peacebuilding aid (excluding Ukraine) between 2021 and 2024 (Figure 13). The Peacebuilding Aid indicator is compiled by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and includes funding in support of conflict prevention and resolution, human rights, security system management and reform, prevention and demobilization of child soldiers, reintegration of combatants, control of small arms and light weapons, removal of land mines and explosive weapons of war, peacekeeping, and other related priorities.

A Civilian First Line of Response: The Growing Importance of Community-Based Protection

When conflicts erupt, civilians are often the first line of response to protection threats. Communities, families, and individuals engage in their own forms of self-protection and community protection, particularly in situations where there is limited state capacity or presence. Such community-based protection (CBP) measures are regularly neglected by external protection actors and donors but have become increasingly recognized in recent years. There is a growing realization that integrating CBP into programming is often the most effective and sustainable response to crises, as it taps into the capacities, knowledge, and agency that already exist at a local level.57 The humanitarian funding crisis that began in 2024 has added new impetus: as resources dwindle and access to communities becomes more difficult, CBP can offer a more cost-effective and locally-grounded way of responding to protection needs.58

CBP approaches can include a wide array of activities. One key function is to empower communities to lead on engagements with armed actors before, during, and after a conflict. Such interactions often happen out of necessity at the community level before any external actors have time to deploy to support more formalized civil-military engagement, mediation, or negotiations. Engagement between civilians and combatants is complex and not always clearcut, particularly because the lines between armed actors and communities can be blurred. Individuals might play roles as influential civilian figures when out of uniform but also operate as part of an armed force. Overlapping social bonds can create an organic environment for negotiations.59 External peace actors can play a crucial role in equipping communities with tools to support such interactions, including through mediation training or by providing platforms for dialogue.

A recent example comes from Yemen, where millions have been displaced and more than 12,400 civilians killed in conflict since 2015. Although high-intensity violence has subsided in some parts of the country, it has continued in areas such as al-Dhale’e, Marib, Taiz, and Lahj. Sporadic clashes and military operations have caused civilian deaths and injuries, and limited movements in search of healthcare or livelihood. To mitigate these harms, CIVIC has worked with local actors to establish Community Protection Groups (CPGs) since 2018 that support communities to engage directly with armed actors on reducing harms. The CPGs are rooted in Yemeni community traditions, and composed of local civil society actors and other leaders, all with a direct tie to the areas in which they work.

These CPGs have taken on a range of functions, including: collecting information on civilian harms at a local level; developing proposed mitigation measures; public awareness raising through media outreach and other events; and strengthening local knowledge of the importance of POC, with a focus on the role of women. In addition, CPGs have brought communities and armed actors together to explore how to collaborate on reducing civilian harms. Such meetings have also provided a forum for raising specific abuses, including arbitrary detentions or harassment at checkpoints. There have been some notable results, including in local dispute resolutions, and in reopening of roads previously closed due to conflict. Such road closures had forced community members to take dangerous alternative routes, while limiting trade and humanitarian access, driving up commodity prices.

Likewise, in 2024, CIVIC-supported CPGs in Nigeria changed military policy and practice through civil-military dialogue in certain conflict-affected areas of the Northeast, including by reversing a harmful decision to ban the use of bicycles on farms, widening the protected town perimeters to create more farming space to accommodate growing town populations, directing military patrols to high-risk areas, and removing soldiers accused of committing sexual exploitation and abuse for follow-up disciplinary action.

Beyond engagement with armed actors, CBP spans a range of other activities, such as efforts to strengthen community preparedness for violence and address social cohesion concerns that drive escalating violence or ignite tensions within communities. In Ukraine, for example, CIVIC worked with CPGs in frontline communities in 2024 to draft Emergency Road Maps outlining activities and roles for responding to escalating security crises in ways that reduce protection threats. Capacity-building on conflict-sensitive communications for CPGs has helped resolve disputes between civilians and demobilized military personnel, or between different social groups (for example, older persons, IDPs, families with mobilized relatives, and parents of children with disabilities.)

Additionally, community-level work is often key to monitoring violations and raising early warning concerns. For example, Comités de veille (“Monitoring committees”) in the Timbuktu, Djenné, and Mopti regions of Mali have facilitated dialogue and information-sharing on protection concerns with local authorities, helping highlight risks faced by civilians and support more responsive security measures. In the DRC, protection monitors work in collaboration with humanitarian actors to identify and report threats, while local watch groups alert authorities to security incidents. The ongoing withdrawal of MONUSCO, however, threatens to undermine some of these systems, as the Mission supported Community Liaison Assistants—who played a key role in liaising between state authorities, armed groups, and villages on security risks—have exited some communities (See Spotlight: UN peacekeeping withdrawals).

Moreover, CBP approaches can provide protection for at-risk or marginalized groups. In South Sudan, Nonviolent Peaceforce has helped establish Women’s Protection Teams that created child-friendly spaces in their communities and played key roles in spreading awareness of waterborne diseases caused by regular flooding.60 Indeed, such climate-focused measures are increasingly becoming a feature of CBP efforts. In the Philippines, peacebuilders have worked with forest rangers to better detect illegal logging and engage with illegal loggers through nonviolent communication to reduce tension. These efforts have also focused on more sustainable ways to manage natural resources, while feeding into early warning systems focused on disaster risk reduction.61

Self-protection initiatives can be an effective way to reduce harm, but they are not without risks, especially when they involve engagement with armed actors. In central Mali, for example, CBP interventions in 2024 allowed communities to negotiate agreements with NSAGs to ensure continued access to markets, livelihoods, and livestock grazing. Such engagement, however, risks falsely stigmatizing communities in the eyes of security forces who suspect them of supporting armed groups. This points to a key challenge in CBP programming: the need to develop risk mitigation measures and ensure that international actors prioritize the safety of local partners. In Ukraine, for example, national frontline responders often absorb the majority of the risks as they deliver aid or engage in protection efforts in areas where INGOs have deemed it too dangerous to deploy international staff. International actors have been criticized for not providing local “subcontractors” with adequate security or protection, effectively failing to meet their duty of care. Recent research by ACAPS and Nonviolent Peaceforce stressed the immediate, practical steps international actors should take, including providing PPE, covering the costs for fuel and vehicle repairs, providing insurance coverage, as well as providing training in safety and security, and relevant international law and standards.62

Moving forward, it is crucial that donors, governments, and practitioners across the humanitarian-peace-development nexus build on recent progress to better integrate CBP approaches across interventions. As a coalition of NGOs led by ICVA recently stressed: in a time of drastically shrinking aid budgets, CBP is not just an ethical imperative but an operational necessity.63 It is crucial that donors ensure that these efforts are prioritized through flexible, multi-year funding, to give efforts time to produce results in the medium- to longer-term. Crucially, this must be done as genuine partnerships where community-based actors have agency and decision-making power, and are not merely subcontractors. Inclusivity is also key, as CBP efforts should include all groups, including marginalized and at-risk members of the community, not just established leaders. Finally, it is important to stress that CBP does not mean leaving local actors to fend for themselves. International partners must establish complementary practices that work in tandem to reinforce, not replace, local efforts.

In 2024 there was a continuation of the ongoing trend in UN peacekeeping toward leaner missions despite continued high risks to civilians, budget constraints, and increasing emphasis on regional arrangements. The UN General Assembly approved a reduced peacekeeping budget for 2024-2025 of $5.38 billion, down 8.2 percent from $6.1 billion in the previous year. This decrease reflects mission closures and a push toward greater efficiency, although UN officials also warned of persistent liquidity and funding challenges.64

Against this backdrop, the Security Council adopted Resolution 2719 in December 2023, formalizing a framework for UN financial support of up to 75 percent of budgets for African Union-led operations.65 UN and AU personnel began the process of operationalizing the resolution in October 2024 with the adoption of a joint roadmap for implementation, although significant political hurdles remained.66 In December, the UNSC endorsed the establishment of the African Union Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM) through Resolution 2767, to be funded through a "hybrid" version of the model set out in Resolution 2719. The US, however, abstained from the vote, citing concerns that the resolution meant the UN would, in practice, fund up to 90 percent of AUSSOM.67

In Haiti, the Kenyan-led Multinational Security Support (MSS) Mission, first approved by the UNSC in October 2023, began operations in 2024. After several delays, the first contingent of Kenyan police officers arrived in Port-au-Prince in June 2024, but only 500 of its mandated 2,500 troops had deployed by the end of the year.68 In September, the UNSC passed a resolution extending the mission for another year. The final text did not include a proposal–supported by the US, Haitian, and other governments–to eventually transform the MSS into a UN peacekeeping operation, largely due to opposition from China and Russia.69 Facing persistent staffing and funding shortfalls, the MSS has struggled to improve the security situation amid escalating gang violence.70 Some analysts, however, noted that the Mission achieved some progress, such as securing ports and other infrastructure.71

UN peacekeeping missions also faced the stark realities of challenging withdrawals amid worsening security conditions and increased hostility from host governments. The UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) completed its withdrawal from South Kivu in June 2024 as part of a broader phased withdrawal plan initially promoted by the Congolese government. However, the government subsequently requested that the second phase be postponed, and the Mission’s mandate extended through 2025 due to escalating violence by armed groups, including the M23.72

In Mali, there were signs that MINUSMA’s exit at the end of 2023 left a security gap in 2024 that NSAGs sought to exploit, highlighting the risk of abrupt mission closure. Armed groups, such as the al Qaeda-affiliated JNIM, significantly expanded territorial control in the Gao and Menaka regions and temporarily seized Bamako’s airport in September.73 Although Malian officials have asserted that the security situation was being effectively managed,74 according to the Mali Protection Cluster, human rights violations increased by 288 percent during the first half of 2024 amid the deteriorating security environment, followed by some improvements later in the year–partly due to intensified operations by the Malian Security Forces.75 At the end of February, The United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS) closed and formally withdrew from the country, as requested by the government and confirmed through the adoption of UNSC Resolution 2715 in 2023.76 The UNITMAS withdrawal also precipitated the closure of the Ceasefire Committee for Darfur and some reduced opportunities for non-UN actors to engage with state authorities on protection issues.77

Despite the broader trend of shrinking UN peacekeeping funds and presence, the approved budgets for military and civilian personnel for the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) and the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) increased moderately in 2024.

Managing the Protection Gap: Challenges from Abrupt Peace Operations Withdrawals

Analysis for this spotlight article is based on a more comprehensive policy brief published by CIVIC, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), and the Global Protection Cluster (GPC) in 2024, titled Protection After UN Peacekeeping Mission Departures.78

As noted, UN peace operations have faced decreased budgets and political support in recent years, leading to withdrawal of staff from several countries, even in contexts where conflict and violations against civilians have continued. Because modern peacekeeping missions are multi-dimensional with expansive mandates, their withdrawals have wide-ranging implications in insecure contexts. Most obviously, the removal of armed blue helmets from an active conflict context can create a major gap in the physical protection of civilians. This “security cliff” is particularly challenging because few other protection actors have the mandates or resources to replicate the range of activities missions undertake—from policing, to training security forces, to logistics. Mission withdrawals also mean that community-based protection models, including early warning systems—such as those developed by missions in the CAR, the DRC, Mali, and South Sudan—may be lost. In Mali, for example, MINUSMA had no time to transfer management of its early warning system amid its rapid withdrawal, while in the DRC, there are concerns about the capacity and funding of state actors to oversee the system MONUSCO is expected to hand over.

The departure of UN missions’ Special Representatives of the Secretary-General (SRSGs) reduces high-level political engagement on protection with national and regional senior leadership. In terms of humanitarian coordination, mission withdrawals can have significant consequences—including the withdrawal of mission POC advisors from the humanitarian cluster system, as well as diminished capacity to support the development of comprehensive national protection strategies. The implications for human rights monitoring can also be severe, as in the case of Mali, where the national government opposed a continued OHCHR presence after MINUSMA’s withdrawal. Even in cases where OHCHR maintains staff in areas where other mission components are no longer present, such as the DRC, they often face reduced resources and access, while risks of reprisals mean it is challenging for national actors to fill this gap. Peace operation closures also have implications for other actors in the protection field—particularly mine action and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) initiatives. Non-mission protection actors also often benefit from the security and logistics support of missions, and their closure can have significant implications for humanitarian access, especially if accompanied by drastic funding cuts to the UN Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS).

At a national level, there are immediate, practical steps donors, protection actors, governments, and others can explore to mitigate the protection risks posed by abrupt withdrawals. These include, for example, strengthening dialogue with armed actors on protection, alongside earlier and ongoing engagement with national authorities on early warning systems during mission deployment. The UN could also consider expanding Resident Coordinator mandates to include engagement with high-level government officials on protection, while also mainstreaming and embedding protection analysis and other functions into UN Country Team frameworks.

More broadly, mission withdrawals could leave remaining protection actors facing a “financial cliff” as they become dependent on less predictable funding streams. To mitigate this, protection actors should consider advocating for more flexible funding arrangements after withdrawals, such as those employed in South Sudan through the Reconciliation, Stabilization, and Resilience Trust Fund (RSRTF). To ease the additional demands on humanitarians following mission departures, protection actors could engage UN entities and donors on options for deploying surge capacities of protection personnel in transition contexts. Some standing capacities already exist through the IASC and UNMAS, which could be leveraged or expanded. Finally, it is crucial to ensure that even in the context of short-term withdrawals, UN missions engage in a structured way with national protection actors on transition plans. In 2024, for example, MONUSCO’s engagement with non-UN actors was limited and began very late in the process of its withdrawal from South Kivu, leading to frustration among NGOs. This can be mitigated by the UN Security Council stressing integrated planning, data-sharing protocols, and early engagement with non-UN actors in mission withdrawal protocols.

In 2024, the UN and partners launched initiatives exploring how to strategically adapt to the changing realities facing peace operations. Member States adopted the Pact for the Future in September, reaffirming their commitment to collaboration with regional organizations while commissioning recommendations for more agile and tailored peace operations.79 Moreover, the Future of Peacekeeping study, commissioned by the UN Department of Peace Operations (DPO), advocated for UN peacekeeping as a “politically focused, people-centered, modular tool” capable of responding rapidly to evolving threats.80 It proposed 30 models for UN missions, ranging from traditional robust stabilization missions to more specialized or hybrid modalities, with a strong emphasis on leveraging new technologies and local engagement. Overall, the study underscored that future UN operations must be more modular and adaptable, as well as better integrated within the UN’s broader prevention and peacebuilding agendas.

From Policy to Practice: Military Efforts to Operationalize the Protection of Civilians

Improving civilian protection requires armed actors to operationalize legal, strategic, and ethical commitments into concrete practice. Many armed actors have taken steps to better embed POC efforts in military operations. Protection and civilian harm mitigation and response (CHMR) measures are wide-ranging and can include—but are not limited to—training of military personnel in IHL and related protection standards, establishing stronger monitoring and oversight mechanisms, improving accountability for violations, and increasing transparency in efforts to combat such harm. In 2024, analysts raised concerns that rapid global militarization and increased arms spending were rarely accompanied by an increased focus on integrating CHMR—although there were also notable positive developments.

The US, throughout 2024, continued to implement CHMR commitments established in the preceding years. Partly in response to a US airstrike in the Afghan capital of Kabul that killed 10 civilians in 2021, the Department of Defense (DoD) released a Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan (CHMR-AP) in August 2022.81 The plan reflected an unprecedented commitment to overhauling US policies for preventing, mitigating, and responding to civilian harm resulting from US military operations. In the two years since its release, an assessment by CIVIC found that the DoD had made progress in putting in place staff and structures aimed at protecting civilians, but that there was still work to be done in implementing the CHMR-AP in practice.82

By 2024, the DoD had hired almost all CHMR-related roles established under the plan and had set up various institutions across the Department to lead on CHMR work, including a new Civilian Protection Center of Excellence (CP CoE). At the combatant command (CCMD) level, new teams were set up to improve analysis of the civilian environment with a view to mitigating harm, as well as cells to oversee civilian harm assessments. The DoD has also initiated the development of new policies and procedures for responding to civilian harm, including acknowledgement, condolence or ex gratia payments, and in-kind and community-level responses. Their impact in practice, however, remains to be seen—despite a $3 million fund for ex-gratia payments, very few payments have been made over the last few years.83

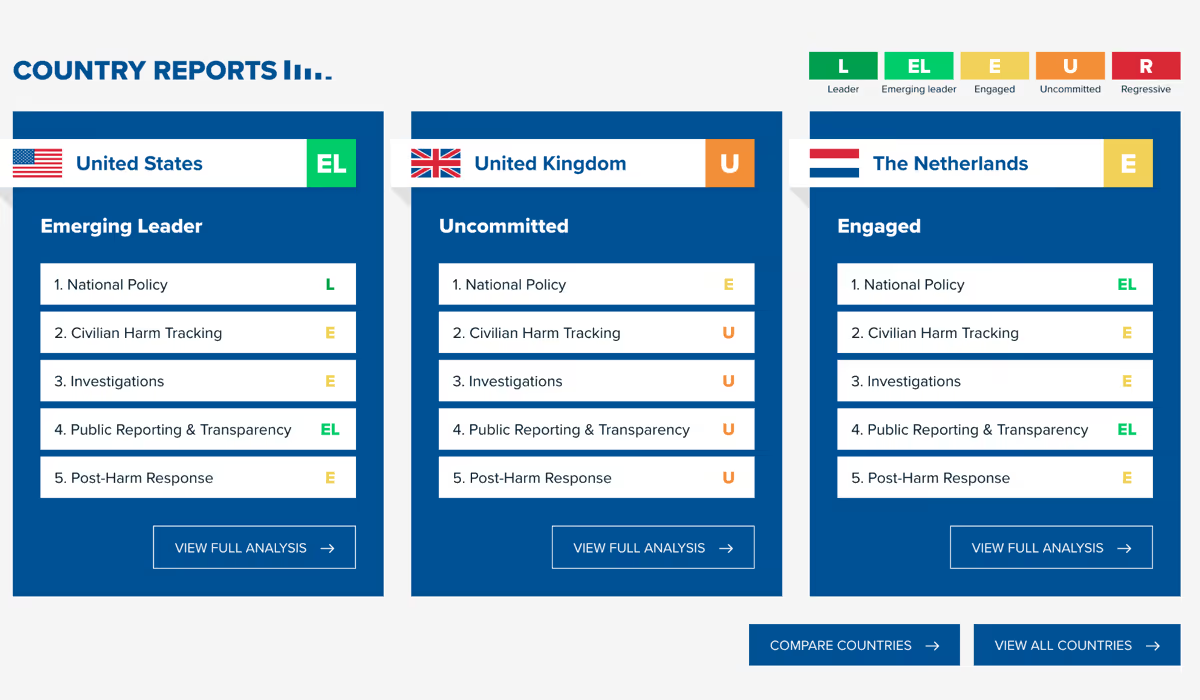

There were notable developments on CHMR in two other NATO member states in 2024. The Netherlands established a centralized civilian harm reporting portal, where civil society and affected civilians can submit reports of alleged harm by Dutch forces.84 This portal builds on previous CHMR efforts by successive governments in the Netherlands, in large part motivated by Dutch air strikes in Iraq in 2019 that killed 89 civilians. Dutch policy, for example, now requires that the government proactively informs Parliament prior to military deployments about the anticipated risks to civilians and mitigation measures.85 The Civilian Protection Monitor—an initiative launched in April 2024 by PAX and Airwars to monitor state policy and practice on protection of civilians—has noted, however, that these efforts mostly apply to Dutch soldiers deployed to international peacekeeping operations, but may not apply if the Netherlands participates in a collective defense operation under NATO’s Article 5.86 The UK, conversely, regressed on CHMR and failed to institutionalize many policy commitments on the protection of civilians. Neither does the UK appear to consistently monitor or investigate reports of civilian harm to internationally recognized standards, while it has also eliminated mechanisms offering voluntary compensation payments to civilians harmed by military operations and introduced legislation to limit such payments.87

The challenges of scaling CHMR policies from counterinsurgency to large-scale warfare came into focus last year, not least due to widespread atrocities in Ukraine since Russia’s full-scale invasion. This issue was also highlighted by the International Contact Group on Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response, an inter-state working group led by the US and the Netherlands, as most CHMR policies originated from counterinsurgency operations in countries such as Afghanistan and Syria.88

The Yemeni military and security leadership from the Aden and Marib governorates advanced their country’s POC tools in March 2024 by signing a POC Code of Conduct Policy. In a November 2024 workshop supported by CIVIC, senior commanders from military and security institutions established an implementation plan that will include dissemination to all military and security sector leaders. It will also strengthen the oversight role of the military police to monitor implementation and establish a supervisory role in the security sectors for the same purpose. The aim is ultimately to involve communities themselves in the oversight and implementation of the plan. The initiative builds on previous engagement by peace actors, including CIVIC, focused on providing platforms for civil-military dialogues with civil society organizations and communities representatives, along with training of security forces in POC and CHMR.89

The Iraqi Prime Minister approved the country’s first National Protection of Civilians Policy which explicitly commits the security and defense forces to respect a range of IHL and IHRL provisions as well as protection principles. These include: a prohibition on torture, excessive use of force, and the use of internationally banned weapons; a commitment to distinguish between combatants and civilians; and a duty to avoid excessive collateral damage. The policy also outlines objectives such as strengthening civilian harm mitigation strategies and mechanisms and striving to compensate civilians for harm.90

In Nigeria, civilian deaths and injuries from military airstrikes have long been a concern. These were not due to deliberate targeting of civilians, but rather misidentification of targets by the military. Such mistakes result from both gaps in technical capacity in the military’s air-to-ground integration (AGI) and the considerable challenges of pursuing NSAG targets that are often closely integrated within local communities.91 In a positive development, the Nigerian military in 2024 took the rare step of prosecuting two officers over an airstrike that led to 80 civilian deaths, although at the end of the year, it had yet to follow up on promises to make public its own investigative report into the incident.92 While US support to the Nigerian military on strengthening CHMR protocols and AGI efforts have been positive, serious gaps remain, according to an assessment by CIVIC. These include a lack of institutional frameworks to apply best practices, scarce reliable intelligence, and the exclusion of military advisors from targeting processes.93 In light of these challenges, other CHMR efforts are critical, including Nigerian military efforts to regularly train military personnel on POC and CHM, empowering military human rights and gender officers to monitor and address violations, and designing codes of conduct.

Moving forward, armed actors must better prioritize and resource CHMR efforts, especially given rapidly rising global arms spending. This should focus on establishing robust and transparent systems for mitigating military harm and ensuring these are incorporated across all military efforts. It is also crucial to ensure that existing CHMR policies are continually updated to reflect new developments in warfare, such as the risks posed by MDMH or the increasing use of explosive weapons in densely populated urban areas.94

Footnotes

- International Committee of the Red Cross, ICRC Annual Report 2024, July 9, 2025.

- UNSC, Report of the Secretary-General on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, UN Doc. S/2025/271.

- Scrolling over a country displays a country profile with information on each component indicator of the Civilian Protection Index. A value closer to zero indicates the poorest performance in a category, while a value closer to 1 indicates the highest performance in a category.

- The 2025 CPI includes methodological enhancements, updated data and more comprehensive time series. When a deviation in ranking from a prior year is noted, please use the information contained in this report.

- "International aid falls in 2024 for first time in six years, says OECD," OECD, April 16, 2025, https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2025/04/official-development-assistance-2024-figures.html

- For the purposes of the Index, North America includes only the US and Canada.

- Per the UN agreed definition, CRSV includes rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity, against women, men, girls, or boys. See United Nations, Handbook for United Nations Field Missions on Preventing and Responding to Conflict-Related Sexual Violence, 2020.

- UNSC, Report of the Secretary-General on Conflict-related Sexual Violence, UN Doc. S/2025/389

- Global Protection Cluster, Annual Report 2024, January 28, 2025.

- Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence Pramila Patten, “GBV against women and girls in conflict, post-conflict and humanitarian settings" (remarks to UN Human Rights Council, Geneva, Switzerland, June 24, 2025), https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/statement/remarks-srsg-patten-at-the-59th-session-of-the-hrc-annual-full-day-discussion-on-the-human-rights-of-women-gbv-against-women-and-girls-in-conflict-post-conflict-and-humanitarian-settings-geneva-2/

- UNSC, Report of the Secretary-General on Conflict-related Sexual Violence, UN Doc. S/2025/389

- UNSC, Resolution 2734 (2024), UN Doc. S/RES/2734 (2024).

- Global Justice Center and UN Women, Documenting Reproductive Violence, September 2024.

- Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel, “More than a human can bear:” Israel's systematic use of sexual, reproductive and other forms of gender-based violence since 7 October 2023, UN Doc. A/HRC/58/CRP.6; Kateryna Busol, "Beyond Sexual – Reproductive and Obstetric Violence in Russia’s Aggression against Ukraine", OpinioJuris, June 7, 2024.

- UN OHCHR, Report of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission for the Sudan, UN Doc. A/HRC/57/CRP.6

- UNSC, Report of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict, UN Doc. A/79/878-S/2025/247

- Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict, UN: New Report Shows 2024 Was the Worst Year Ever for Children Living in Armed Conflicts, June 20, 2025; Joint open NGO Letter to the Secretary-General on the 2025 Annual Report on Children and Armed Conflict, May 28, 2025.

- ACLED, Mapping al-Shabaab's activity in Somalia in 2024, December 13, 2024.

- “Somalia beach attack kills 37 civilians, minister says”, Reuters, August 5, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/explosion-goes-off-beach-somali-capital-prime-minister-says-2024-08-02/

- ACLED, Mapping al-Shabaab's activity in Somalia in 2024.

- Caleb Weiss, “Analysis: Shabaab mounts large-scale offensive, Somali Armed Forces claim victory”, FDD’s Long War Journal, July 23, 2024.

- UNOCHA Somalia, Humanitarian Access Snapshot: January – December 2024, January 22, 2025.

- ACLED, Mapping al-Shabaab's activity in Somalia in 2024.

- UNHCR, Somalia, Flash Alert #14: Jubbaland Forces Conflict with Al-Shabaab in Villages Surrounding Afmadow District Displaces Approximately 1,800 Individuals, July 24, 2024; UNHCR Somalia, Flash Alert 15: Over 1,620 Individuals Displaced from Bullo-Haji Arrive in Kismayo Following Recent Clashes between Jubbaland Forces and Al- Shabaab, August 1, 2024.

- Somalia Protection Cluster, Joint Protection and Shelter Frontline Response Kismaayo & Afmadow Districts, Jubaland State, July 2024.

- Safeguarding Healthcare in Conflict, Epidemic of Violence: Violence Against Health Care in Conflict 2024, April 2025.

- UN OCHA, Reported impact snapshot: Gaza Strip, December 17, 2024; Global Education Cluster, Verification of damages to schools based on proximity to damaged sites - Gaza, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Update #6, September 2024.

- "Attacks on Education in Ukraine Double in 2024," Save the Children, January 23, 2025, https://www.savethechildren.net/news/attacks-education-ukraine-double-2024-leaving-some-parents-terrified-send-their-children

- The SSD is an inter-governmental political commitment to protect students, teachers, schools, and universities from the worst effects of armed conflict. For more information, see: https://ssd.protectingeducation.org/endorsement/

- UNHCR, Global Trends Report 2024.

- IDMC, "Displacement, disasters and climate change," accessed September 1, 2025, https://www.internal-displacement.org/focus-areas/Displacement-disasters-and-climate-change/.

- UNHCR, Global Trends Report 2024.

- UNHCR, Returns to Afghanistan, May 28, 2024; UNHCR, "Where We Work: Afghanistan", accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.unhcr.org/where-we-work/countries/afghanistan Amnesty International and International Commission of Jurists, The Taliban’s war on women: The crime against humanity of gender persecution in Afghanistan, May 25, 2023.

- World Food Programme, 2025 Global Outlook, November 2024.

- "Gaza: Israel’s Imposed Starvation Deadly for Children," Human Rights Watch, April 9, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/04/09/gaza-israels-imposed-starvation-deadly-children "Using starvation as a weapon of war in Sudan must stop: UN experts," UN OHCHR, June 26, 2024. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/06/using-starvation-weapon-war-sudan-must-stop-un-experts "‘Are we not eating tonight?’ Myanmar’s military junta accused of using hunger as a ‘weapon’ by blocking vital food aid," CNN, August 25, 2024, https://edition.cnn.com/2024/08/23/asia/myanmar-junta-blocking-food-aid-intl-hnk

- "ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I rejects the State of Israel’s challenges to jurisdiction and issues warrants of arrest for Benjamin Netanyahu and Yoav Gallant," ICC, November 21, 2024, https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/situation-state-palestine-icc-pre-trial-chamber-i-rejects-state-israels-challenges

- Chase Sova, "Starvation Crimes and International Law: A New Era", Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 4, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/starvation-crimes-and-international-law-new-era

- EWIPA, "List of endorsing states," accessed September 1, 2025, https://cms.ewipa.org/uploads/List_of_Endorsing_States_EWIPA_as_of_26_May_2025_8fa1c5b164.pdf

- First international follow-up conference to EWIPA Declaration, "Outcome statement and recommendations for the way forward," December 2024, https://cms.ewipa.org/uploads/EWIPA_Troika_Outcome_Statement_8cc0c54c94.pdf

- Explosive Weapons Monitor, Annual Report 2024, May 2024.

- Cluster Munition Coalition, Cluster Munition Monitor 2025, September 2025; Lauren Spink, ”Extracting Lessons from the Russia-Ukraine War to Improve Civilian Protection,” Lieber Institute Articles of War, January 30, 2025, https://lieber.westpoint.edu/extracting-lessons-russia-ukraine-war-improve-civilian-protection/

- UNESCO, "Statistics on Killed Journalists," accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.unesco.org/en/safety-journalists/observatory/statistics?hub=72609 "Journalists killed in 2024: a heavy death toll in conflict zones for the second year running," UNESCO, December 12, 2024, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/journalists-killed-2024-heavy-death-toll-conflict-zones-second-year-running

- UNSC, Report of the Secretary-General on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, UN Doc. S/2025/271

- "2024 is deadliest year for journalists in CPJ history; almost 70% killed by Israel," Committee to Protect Journalists, February 12, 2025, https://cpj.org/special-reports/2024-is-deadliest-year-for-journalists-in-cpj-history-almost-70-percent-killed-by-israel/

- SIPRI, Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024, April 2025.

- Institute for Economics and Peace, Global Peace Index 2025, June 2025.

- Aid Worker Security Database, Aid Worker Security Report 2025, August 2025.

- UNSC, Resolution 2730 (2024), UN Doc. S/RES/2730 (2024).

- UNSC, Letter dated 22 November 2024 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc. S/2024/852.

- ACAPS, Humanitarian Access Overview: Spotlight on violence against aid workers, December 2024.

- UNSC, Report of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict, UN Doc. A/79/878-S/2025/247

- CIVICUS, “Global Summary of 2024 CIVICUS Monitor,” accessed September 1, 2025, https://monitor.civicus.org/globalfindings_2024/innumbers/

- UNSC, Note by the Secretary-General on Protecting the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association from Stigmatization, UN Doc. A/79/263.

- ALNAP, Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2025, June 2025.

- Global Protection Cluster, GPC Funding Analysis and Protection Risks - Understanding the Link and the Cost of Inaction, April 15, 2025.

- "International aid falls in 2024 for first time in six years, says OECD," OECD, April 16, 2025, https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2025/04/official-development-assistance-2024-figures.html

- In 2025, for example, UNHCR issued guidance recommending the integration of community-based approaches in “in all phases of humanitarian response programmes, across all sectors and in all humanitarian contexts.” UNHCR, Community-Based Protection (CBP), January 27, 2025.

- ICVA et. al., "NGO Statement on Community-Based Protection," June 18, 2025. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/ngo-statement-community-based-protection

- Humanitarian Practice Network, Community engagement, protection and peacebuilding: reviewing evidence and practice, January 16, 2023.

- Nonviolent Peaceforce, Responding to Crisis Multiplied: Climate, Conflict, and Unarmed Protection Civilian, n.d..

- Nonviolent Peaceforce, Responding to Crisis Multiplied: Climate, Conflict, and Unarmed Protection Civilian, n.d.. https://nonviolentpeaceforce.org/wp-content/uploads/archive/Publications/Briefs/Climate_Crisis_UCP.pdf

- Nonviolent Peaceforce, Localisation in Practice: Implementing Responsible Humanitarian Partnerships in Ukraine, November 2024.

- ICVA et. al., "NGO Statement on Community-Based Protection."

- "$5.4 billion UN peacekeeping budget approved for 2025-2026," UN News, July 4, 2025, https://www.un.org/en/delegate/54-billion-un-peacekeeping-budget-approved-2025-2026

- For background, see the Protect section of CIVIC’s POC Trends Report 2023.

- “March 2025 Monthly Forecast," Security Council Report, March 1, 2025. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2025-03/un-peacekeeping-14.php

- US Mission to the UN, Explanation of Vote Following the Adoption of a UN Security Council Resolution Renewing the Mandate of AUSSOM, December 27, 2024.

- SIPRI, Developments and Trends in Multilateral Peace Operations, 2024, May 2025.

- "Haiti: Vote to Renew the Authorisation of the Multinational Security Support Mission," Security Council Report, September 29, 2024, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2024/09/haiti-vote-to-renew-the-authorisation-of-the-multinational-security-support-mission.php

- International Crisis Group, Locked in Transition: Politics and Violence in Haiti, February 19, 2025.

- Ibid.

- "Armed groups install ‘parallel administration’ in DR Congo, Security Council hears," UN News, March 27, 2025, https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/03/1161621

- "December 2024 Monthly Forecast," Security Council Report, December 1, 2024, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2024-12/west-africa-and-the-sahel-13.php

- "Terrorists and their foreign sponsors, though ‘weakened’ still pose a threat, Mali minister warns," UN News, September 28, 2024, https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/09/1155136

- Global Protection Cluster, Mali Protection Analysis Update, August 12, 2024; Global Protection Cluster, Mali Protection Analysis Update, June 5, 2024.

- "With the closure of UNITAMS, the Special Representative urges support to close gaps in child protection capacity and funding in Sudan," OSRSG CAAC, February 7, 2024, https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/closure-unitams-special-representative-urges-support-close-gaps-child-protection-capacity-and-funding-sudan

- CIVIC, Norwegian Refugee Council, and the Global Protection Cluster, Protection After UN Peacekeeping Mission Departures, June 18, 2025.

- Ibid.

- UN General Assembly, Pact for the Future, UN Doc. A/RES/79/1, September 2024.

- UN Peacekeeping, The Future of Peacekeeping, New Models, and Related Capabilities, November 2024.

- "DoD: August 29 Strike in Kabul 'Tragic Mistake,' Kills 10 Civilians," US Department of Defense, September 17, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2780257/dod-august-29-strike-in-kabul-tragic-mistake-kills-10-civilians/ US Department of Defense, Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan (CHMR-AP), August 25, 2022.

- CIVIC, Tracking Implementation of the Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan (CHMR-AP), October 31, 2024.

- Civilian Protection Monitor, Country Report: United States 2024, April 2025.

- The Netherlands Ministry of Defence, "Reporting civilian harm", accessed on September 1, 2025, https://english.defensie.nl/topics/c/civilian-casualties/reporting-civilian-harm

- Lucca de Ruiter, Erin Bijl and Megan Karlshoej-Pedersen, "In Preparing for Large-Scale Conflicts, States Neglect Lessons on Civilian Protection at Their Peril," Just Security, August 14, 2025, https://www.justsecurity.org/118838/civilian-protection-large-scale-conflict/

- Civilian Protection Monitor, Country Report: The Netherlands 2024, April 2025. https://civilianprotectionmonitor.org/country/netherlands/

- Civilian Protection Monitor, Country Report: United Kingdom 2024, April 2025.

- "Readout of International Contact Group Meeting on Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response," US Deptartment of Defense, September 24, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3915930/readout-of-international-contact-group-meeting-on-civilian-harm-mitigation-and/

- CIVIC, "Protection of Civilians in Yemen," accessed on September 1, 2025, https://civic.shorthandstories.com/yemen/index.html

- Republic of Iraq Prime Minister Office, National Protection of Civilians Policy in Iraq, 2024.

- CIVIC, US Security Assistance to Nigeria: Civilian Protection Gaps and Opportunities, June 2024.

- "Why do civilians often die in Nigerian military strikes that target rebels?," Associated Press, January 15, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/nigeria-military-airstrike-civilian-casualties-rebels-4103543b005bf448d951628fcf45fe9f

- CIVIC, US Security Assistance to Nigeria: Civilian Protection Gaps and Opportunities.

- Sahr Muhammedally, "Understanding Risks and Mitigating Civilian Harm in Urban Operations," Canadian Army Journal, October 2024.